Abstract

-

Background

Progressive osteoporosis reduces the trabecular structures of the proximal femur, whereas the primary compression trabeculae (PCTs) are relatively preserved. We hypothesize that the loss of the vertically oriented PCTs in osteoporosis, which act as a mechanical barrier, affects fracture line propagation and influences the Pauwels angle. This study investigated the association between bone mineral density (BMD) and Pauwels angles in low-energy femoral neck fractures (FNFs).

-

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 150 patients (mean age, 75.3 years; range, 50–94 years) diagnosed with intracapsular FNFs between May 2019 and May 2023. BMD was measured within 1 month of the injury date using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, and modified Pauwels angles were assessed using a computed tomography-based multiplanar reconstruction program. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate the factors influencing the Pauwels angles. The dependent variable was the Pauwels angle, while the independent variables included sex, age, height, body weight, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, Charlson comorbidity index score, smoking status, alcohol use, preinjury walking ability, and femoral neck BMD T-scores.

-

Results

Higher femoral neck BMD T-scores were significantly associated with increased Pauwels angles (B=3.449, P<0.001). Greater body weight was independently associated with increased Pauwels angles (B=0.213, P=0.007).

-

Conclusions

The Pauwels angle demonstrated a significant association with BMD, with lower BMD associated with less steep Pauwels angles. In the absence of BMD measurement, the Pauwels angle may indicate osteoporosis severity in patients with low-energy FNFs.

-

Level of evidence

III.

-

Keywords: Body mass index, Femoral neck fracture, Osteoporosis, Bone density, Biomechanical phenomena

Introduction

Background

The global incidence of hip fractures is increasing rapidly due to population aging, with femoral neck fractures (FNFs) accounting for approximately 49%–53% of hip fractures [

1,

2]. By 2050, hip fractures are projected to double that of 2018, presenting significant socioeconomic and healthcare challenges [

3,

4]. In the older population, nearly 90% of hip fractures result from low-energy trauma, a major consequence of osteoporosis [

5-

7].

The demographic shift raises medicolegal challenges. It requires distinguishing whether fractures are caused by trauma or osteoporosis-related fragility, particularly when osteoporosis is cited to justify reduced compensation [

8]. However, without dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans performed near the time of injury, assessing the contribution of osteoporosis to fractures remains challenging.

Osteoporosis is characterized by reduced bone mineral density (BMD) and a weakened trabecular structure [

9,

10]. As osteoporosis progresses, the trabecular structures in the proximal femur gradually diminish; however, the primary compression trabeculae (PCT)—the principal load-bearing structure—are the least affected [

11,

12]. Nevertheless, their eventual degradation significantly reduces the bone strength in the PCT region [

12]. Biomechanical studies of human bones indicate that fracture propagation typically follows paths requiring minimal energy, either through structural weak points near barriers such as osteons or parallel to the bone’s longitudinal axis, potentially influencing fracture patterns [

13-

15].

Therefore, the vertically oriented PCT may act as mechanical barriers, potentially redistributing the stress and guiding the fracture lines. Thus, higher BMD, supported by dense PCT, is hypothesized to guide fracture lines more vertically, resulting in increased Pauwels angles. In contrast, with decreasing BMD, these structural constraints weaken, leading to more horizontal fracture lines and decreased Pauwels angles.

Objectives

The association between decreased BMD and fracture risk is well established [

16,

17]. However, the effect of low BMD on fracture morphology, particularly its influence on the Pauwels angle in low-energy FNFs, remains underexplored. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the association between BMD and the Pauwels angle in low-energy FNFs. We hypothesize that a lower BMD is associated with less steep (decreased) Pauwels angles.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Inje University Busan Paik Hospital (IRB No. 2025-01-010). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB because of the retrospective design and use of anonymized data.

Study design

It was a cross-sectional study. It was described according to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement available at:

https://www.strobe-statement.org/.

This study was conducted at Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea.

Participants

Data from 262 patients diagnosed with intracapsular FNFs between May 2019 and May 2023 were retrospectively reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of subcapital or transcervical FNFs; age ≥50 years; and fractures resulting from low-energy trauma. The exclusion criteria were as follows: pathologic fractures; absence of BMD assessment within 1 month of injury or no BMD measurement performed; history of contralateral hip surgery causing implant artifacts; and contralateral hip bone deficits following implant removal, leading to artifacts that affect BMD measurements. Fractures caused by ground-level falls were defined as low-energy fractures [

18]. After excluding patients, 150 patients were enrolled in this study.

The primary outcome variable was the modified Pauwels angle measured on CT-based multiplanar reconstruction images. The main exposure of interest was femoral neck BMD (T-score), and potential confounders included age, sex, height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [

19], smoking status, alcohol use, and preinjury walking ability (categorized as independent or not independent).

Data were selected from the electronic medical records of the Inje University Busan Paik Hospital.

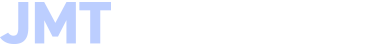

Modified Pauwels angle measurement

The RadiAnt DICOM Viewer (Medixant) was used to import computed tomography (CT) Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine files and generate three-dimensional multiplanar reconstruction images to assess the lower extremity deformities associated with the fracture and establish the mid-coronal plane. In the axial plane, the head-neck axis (HNA) was determined using a line of the best-fit method through the center of the femoral neck isthmus to correct the external rotation deformity and femoral neck anteversion [

20]. The mid-coronal plane was constructed as the plane containing the HNA and orthogonal to the axial plane, bisecting the femoral neck into the anterior and posterior regions. In the sagittal plane, the anatomical axis of the proximal femur was used to adjust the alignment of the mid-coronal plane to correct the lower extremity deformity and restore anatomical alignment. The Pauwels angle was measured on the reconstructed mid-coronal plane as the angle between the fracture line and a line perpendicular to the central line of the femoral shaft using a modified method (

Fig. 1) [

20,

21]. The modified Pauwels angles were measured by two orthopedic surgeons who performed repeated measurements on the same images with a 3-week interval to assess intraobserver reliability. Consistency among raters was evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), interpreted as <0.5 indicating poor reliability; 0.5–0.75, fair reliability; 0.75–0.9, good reliability; and >0.9, excellent reliability. In this study, the ICC values for the intra- and interobserver reliabilities ranged from 0.751 to 0.824 (

Table 1).

BMD assessment

BMD measurements were performed using the Hologic Horizon W DXA Scanner (Hologic Inc.). Femoral neck BMD T-scores were assessed from the contralateral hip, assuming that it provides a reliable estimate of the BMD on the injured side. All measurements were conducted within 1 month of the injury to minimize temporal changes [

22]. In this study, the World Health Organization’s definitions of osteoporosis were used: T-scores ≥−1 represent normal BMD, T-scores between −1 and −2.5 indicate osteopenia, and T-scores ≤−2.5 define osteoporosis [

23].

To reduce selection bias, all eligible consecutive patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria during the study period were included. Measurement bias was minimized by using a standardized CT-based protocol for Pauwels angle measurement and by performing BMD assessments with a single DXA scanner within one month of injury.

Study size

No formal sample size calculation was performed; instead, the study included all eligible patients with low-energy intracapsular FNFs treated at our institution between May 2019 and May 2023.

Quantitative variables

Age, body weight, BMI, and Pauwels angle were treated as continuous variables in the regression analyses, whereas preinjury walking ability was entered as a binary categorical variable (independent vs. not independent).

Statistical methods

IBM SPSS ver. 27.0 (IBM Corp.) was used for the statistical analysis. Significance was set at P<0.05. Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the factors that affect the Pauwels angles. The dependent variable was the Pauwels angle, while the independent variables included sex, age, height, body weight, BMI, ASA score, CCI score, smoking status, alcohol use, preinjury walking ability, and femoral neck BMD T-scores. Forward stepwise logistic regression was performed to construct an osteoporosis prediction model incorporating the Pauwels angle.

There were no missing data for the variables included in the regression analyses. No subgroup, interaction, or sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results

Participants

The patient flow chart is shown in

Fig. 2.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in (

Table 2). Among the 150 patients, women comprised 69.3%, and the mean age was 75.3 years (range, 50–94 years). The mean femoral neck BMD T-score was −2.6 (range, −4.5 to −0.4). According to the WHO criteria, 96.7% of the patients exhibited either osteopenia (40.7%) or osteoporosis (56.0%). The mean Pauwels angle was 58.5° (range, 38.7°–78.7°). Most fractures were displaced and classified as Garden types 3 or 4 (89%).

Multiple linear regression analysis (R²=0.200) demonstrated that femoral neck BMD T-scores (B=3.449, P<0.001) and body weight (B=0.213, P=0.007) were significantly associated with the Pauwels angle (

Table 3). No variable exhibited a variance inflation factor ≥2, indicating the absence of multicollinearity. Higher femoral neck BMD T-scores and greater body weight were independently associated with an increase in the Pauwels angle in low-energy FNFs (

Fig. 3).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified the Pauwels angle, sex, and age as significant independent predictors of osteoporosis in low-energy FNFs (all P<0.001) (

Table 4). The receiver operating characteristic curve combining these factors yielded an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.839 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.774–0.904; P<0.001), with a sensitivity of 81% (95% CI, 0.631–0.929) and a specificity of 77% (95% CI, 0.424–0.849) (

Fig. 4). The model development and internal validation are described in the

Supplement 1, and the calibration curve and nomogram are shown in

Supplements 2 and

3, respectively.

Discussion

Key results

Among 150 participants, 96.7% had osteopenia or osteoporosis. The mean Pauwels angle was 58.5°. Linear regression showed femoral neck BMD T-scores (B=3.449, P<0.001) and, body weight (B=0.213, P=0.007) were significantly linked to the Pauwels angle. Multivariate analysis identified Pauwels angle, sex, and age as independent osteoporosis predictors. The combined model achieved an area under the curve of 0.839, with 81% sensitivity and 77% specificity. These results demonstrate the Pauwels angle correlates with bone density and effectively predicts osteoporosis in patients with low-energy FNFs.

Interpretation/comparison with previous studies

Fractures typically propagate along paths requiring the least energy, often following structural weak points [

13-

15]. Nalla et al. [

14] demonstrated that cracks in the cortical bone propagate along osteons, which act as structural barriers. Similarly, Taylor et al. [

15] reported that in the cancellous bone, microcracks align with the bone’s longitudinal axis, whereas cortical bone cracks encountering barriers such as osteons change direction. In the proximal femur, the PCT likely acts as a similar mechanical barrier, redistributing the stress to guide fracture propagation. Our findings support this mechanism. When BMD is high, preserved PCT guide fracture lines vertically, leading to steeper Pauwels angles. As osteoporosis progresses, PCT are lost and these barriers weaken. This is consistent with the decreased Pauwels angles observed in patients with low BMD (

Fig. 5).

Osteoporosis significantly increases the risk of hip fractures due to BMD reduction and trabecular deterioration [

9,

10,

16,

17]. Recent quantitative studies have shown that PCT is least affected by osteoporosis-induced changes compared with other trabecular regions [

11,

12]. Bot et al. [

11] reported that Ward’s triangle showed the most significant resorption, whereas the PCT remained relatively preserved. Feng et al. [

12], using micro-CT and finite-element analysis, confirmed that PCT degradation occurs more slowly than in other regions, reducing bone strength in the PCT. However, no direct biomechanical studies have validated the relationship between trabecular loss and fracture propagation. Thus, future studies using advanced imaging and biomechanical models are needed to confirm this relationship.

This study also identified a significant positive association between body weight and Pauwels angles. Although the injury mechanism differs from that of high-energy trauma commonly seen in young adults with FNFs, which is associated with vertical Pauwels angles—such as an automobile accident or a fall from a great height, where direct axial loading is transmitted along the femur to the pelvis [

20,

24]—it highlights how greater body weight in low-energy mechanisms, like a lateral fall from standing height, can influence fracture patterns through increased trauma energy. Increased body weight contributes to greater trauma energy during falls, as described by the equations for kinetic and potential energy. Mechanically, this suggests that a higher body weight increases the force transmitted to the femoral neck, potentially resulting in steeper Pauwels angles. Although protective factors such as muscle mass or subcutaneous padding may mitigate this force, they are likely insufficient to counteract the dominant effect of trauma energy. Furthermore, the specific contributions of the body composition remain unclear, complicating its protective role [

25]. These findings underscore body weight as an independent determinant of fracture morphology, distinct from the previously established association between lower body weight, BMI, and fracture risk [

26-

28].

To the best of our knowledge, only one study has used a CT-based image reconstruction program for accurately measuring the modified Pauwels angle, which effectively eliminates projection errors. Kong et al. [

21] included patients aged <65 years and measured the modified Pauwels angle regardless of the trauma energy. In the reformatted CT coronal images, the average Pauwels angle was 68.7° (all classified as Pauwels type II or III). In contrast, the present study reported a lower average Pauwels angle of 58.5° (range, 38.7°–78.7°), which likely due to the older patient cohort and inclusion of only low-energy trauma cases.

In this study, the highest Pauwels angle was 78.7°. Recently, Xu et al. [

29] conducted a CT-based quantitative analysis of PCT among the elderly and reported a minimum PCT angle of 3.44°, relative to the proximal anatomical femoral axis. When adjusted for comparison with the modified Pauwels angle, this corresponded to 93.44°, which is comparable to the highest Pauwels angle observed in this study and to the highest angle (91.2°) reported by Kong et al. [

21]. While a direct numerical match is not expected due to variability in fracture propagation, these findings support the hypothesis that a dense PCT, indicative of higher BMD, acts as a barrier to fracture propagation along or within the original PCT axis. Pauwels type I fractures (<30°) are exceptionally rare. Given the inclination of the femoral neck axis relative to the proximal anatomical femoral axis, defined as the neck shaft angle, such low-angle fractures would require an unusual trajectory involving the greater trochanter or medial extension to the femoral head. Although some biomechanical models reference Pauwels angles of 30°, to our knowledge, no clinical cases of type I fractures measured using reformatted CT planes have been reported, aligning with our findings [

30,

31].

Previous studies evaluating Pauwels angle or fracture morphology in osteoporotic FNFs are limited. Thirunthaiyan et al. [

32] reported that transcervical fractures were more frequent in patients with Singh index 4, whereas subcapital fractures predominated in those with Singh index 3. Similarly, Heetveld et al. [

33] similarly demonstrated that the proportion of Pauwels type III fractures was higher in patients with normal BMD or osteopenia compared to those with osteoporosis. These results are in partial agreement with our findings, suggesting that increasing osteoporosis severity is associated with lower Pauwels angles. In contrast, Zhao et al. [

34] reported a decreasing trend of Hounsfield units and femoral cortical index across Pauwels types I to III. However, these prior studies were limited by simple comparative analyses and relied on radiographic measurements rather than CT-based reformatted assessments of fracture classification.

In the present study, 96.7% of patients had either osteopenia or osteoporosis. Dhibar et al. [

35] reported that 97.3% of patients with fragility hip fractures had either osteoporosis or osteopenia, while Bartels et al. [

36] demonstrated comparable rates in osteoporotic FNFs (44% osteoporosis and 47% osteopenia). These findings highlight the consistently high prevalence of impaired bone quality in this population.

In this study, contralateral hip BMD was used because the fractured side cannot be reliably assessed at the time of injury. Previous studies indicate that although contralateral hips show high correlations in BMD, clinically meaningful asymmetries can still occur, limiting the precision of using one hip’s BMD to represent the other. Yang et al. [

37] reported strong correlations between contralateral hips, with coefficients ranging from 0.893 to 0.9 across the femoral neck, trochanter, and Ward’s triangle. In contrast, Mounach et al. [

38] found that in a cohort of 3,481 subjects, 52.1% of femoral neck measurements showed differences exceeding the smallest detectable difference. Lilley et al. [

39] similarly demonstrated high correlation coefficients (0.91 for the femoral neck, 0.91 for Ward’s triangle, and 0.84 for the trochanter), yet observed variations of up to 34% at the femoral neck, 64% at Ward’s triangle, and 80% at the trochanter. Therefore, although contralateral BMD is widely used in fragility hip fracture research as a practical alternative [

22,

40], potential side-to-side differences should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings.

This study has several limitations. First, the R² value was 0.200 in the regression analysis, indicating that only 20% of the variance in Pauwels angle could be explained by the T-score and body weight. This limited explanatory power reduces its utility as a precise quantitative tool, and therefore, the results of this study must be interpreted cautiously. This limitation is likely due to individual variations in the proximal femoral geometry, fall direction and velocity, and PCT distribution. However, multivariate logistic regression analysis identified the Pauwels angle as a significant independent predictor of osteoporosis, alongside sex and age. A predictive model incorporating these factors demonstrated an AUC of 0.839, suggesting the Pauwels angle as a reliable predictor of osteoporosis in low-energy FNFs. Second, the retrospective, single-center design limit generalizability, and incomplete BMD data may introduce bias. Third, the BMD was measured from the contralateral hip, assuming that the BMD of the injured hip is likely similar to that of the uninjured site. Although this approach may have introduced bias, accurately measuring the BMD of the injured hip directly remains challenging. Local changes in BMD may occur over time, particularly after fractures and decreased ambulatory activity following surgery. To minimize the influence of temporal changes, our BMD measurements were obtained from the contralateral hip within one month following the fracture. Fourth, direct biomechanical validation of the relationship between BMD-related trabecular loss and fracture propagation was not performed. Future multicenter studies and biomechanical models using high-resolution imaging, such as micro-CT and finite-element analysis, are warranted to validate these findings. Fifth, this study should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating, and the findings will require confirmation in larger prospective studies.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates that the Pauwels angle is significantly associated with BMD, with lower femoral neck T-scores corresponding to less steep angles. The predictive model incorporating the Pauwels angle demonstrated promising results, further supporting its role as a reliable osteoporosis predictor. These findings suggest that the Pauwels angle could serve as an alternative indicator of bone fragility and BMD in low-energy FNFs at the time of injury.

Clinical implication

In South Korea, orthopedic experts are often required to determine whether FNFs in elderly patients are attributable to osteoporosis or to trauma itself. Our results suggest that basic demographic factors (age, sex) combined with fracture morphology, especially the Pauwels angle, can provide useful probabilistic estimates of underlying osteoporosis. This approach may assist orthopedic experts in providing evidence-based opinions in medicolegal and insurance disputes where only limited clinical data are available.

Conclusions

There was a significant association between the Pauwels angle and BMD in low-energy FNFs. Osteoporosis-related changes in PCT may influence fracture patterns. The Pauwels angle, combined with basic demographic factors, may serve as a practical surrogate marker of underlying osteoporosis when BMD assessment is unavailable.

Article Information

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: SHJ. Data curation: JHP. Formal analysis: YUK. Investigation: SHJ. Methodology: YUK. Project administration: YUK. Software: JHP. Supervision: SHJ. Validation: YUK. Visualization: JHP. Writing-original draft: SHJ. Writing-review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for data availability.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

Supplementary material

Fig. 1.Modified Pauwels angle measurement using multiplanar reconstruction. (A) The head-neck axis (HNA; pink line) was identified in the axial plane using the line of the best-fit method through the center of the femoral neck isthmus. This process corrected the external rotation deformity and femoral neck anteversion. The mid-coronal plane was defined as the plane containing the HNA and oriented perpendicular to the axial plane, dividing the femoral neck into anterior and posterior regions. (B) The sagittal plane was utilized to adjust the alignment of the mid-coronal plane using the anatomical axis of the proximal femur. This adjustment corrected the lower extremity deformities and restored proper anatomical alignment. (C) The modified Pauwels angle was measured on the reconstructed mid-coronal plane as the angle between the fracture line (green line) and a line perpendicular (yellow line) to the central line of the femoral shaft (blue line). A 79-year-old female patient with a femoral neck T-score of −1.7 sustained a ground-level fall, resulting in a modified Pauwels angle of 71.2°. (D) In contrast, an 83-year-old female patient with a femoral neck T-score of −4.2 exhibited a modified Pauwels angle of 47.9° in the reconstructed mid-coronal plane.

Fig. 2.Flowchart of patient selection. BMD, bone mineral density.

Fig. 3.Association between femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) T-scores, body weight, and the Pauwels angle using multiple regression models. (A) Three-dimensional scatter plot showing the relationship between the T-score, body weight, and Pauwels angle with a regression surface. (B) Scatter plot of the T-score versus Pauwels angle, with a regression line fitted while the body weight is fixed at its mean value (56 kg). (C) Scatter plot of body weight versus the Pauwels angle, with a regression line fitted while the T-score is fixed at its mean value (−2.6). All individual data points are displayed.

Fig. 4.Receiver operating characteristic curve for the combined model incorporating the Pauwels angle, sex, and age in predicting osteoporosis (area under the curve, 0.839).

Fig. 5.Relationship between the Pauwels angle and bone mineral density (BMD). (A) Radiograph of a female patient with relatively high BMD (T-score, −1.5). The preserved primary compression trabeculae (PCTs) are associated with a vertically oriented fracture line, resulting in a steeper Pauwels angle. (B) Radiograph of a female patient with low BMD due to advanced osteoporosis (T-score, −4.5). Loss of PCTs leads to a more horizontally oriented fracture line and a decreased Pauwels angle.

Table 1.Intraobserver and interobserver reliability for modified Pauwels angle measurements

|

Observer |

Intraobserver reliability (95% CI) |

Interobserver reliability (95% CI) |

|

A |

0.817 (0.747–0.869) |

0.751 (0.657–0.820) |

|

B |

0.824 (0.757–0.872) |

Table 2.Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (n=150)

|

Characteristic |

Value |

|

Sex (male:female) |

46:104 |

|

Age (yr) |

75.3±9.7 (50–94) |

|

Involved hip (right:left) |

82:68 |

|

Height (cm) |

160.1±8.5 (143–187) |

|

Weight (kg) |

56.0±9.5 (34–80) |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

21.9±3.3 (13.6–32.5) |

|

ASA score |

2.6±0.5 |

|

CCI |

4.0±1.4 |

|

Smoking |

38 (25.3) |

|

Alcohol use |

25 (16.7) |

|

Preinjury walking ability |

|

|

Independent |

96 (64) |

|

Not independent |

54 (36) |

|

BMD T-score, femoral neck |

–2.6±0.8 (−4.5 to −0.4) |

|

WHO definition |

|

|

Normal |

5 (3.3) |

|

Osteopenia |

61 (40.7) |

|

Osteoporosis |

84 (56.0) |

|

Pauwels angle (°) |

58.5±9.3 (38.7–78.7) |

|

Garden type (1/2/3/4) |

4/12/32/102 |

Table 3.Multiple linear regression analysis of factors affecting the Pauwels angle (°) using the stepwise method

|

Independent variable |

Unstandardized coefficient |

Standardized coefficient (β) |

P-value |

|

B |

SE (B) |

|

BMD T-score (femoral neck) |

3.449 |

0.88 |

0.314 |

<0.001 |

|

Weight (kg) |

0.213 |

0.078 |

0.219 |

0.007 |

Table 4.Multivariate logistic regression analysis identifying independent predictors of the presence of osteoporosis (yes/no)

|

Independent variable |

OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

|

Pauwels angle (°) |

0.91 (0.87–0.96) |

<0.001 |

|

Sex (female; reference, male) |

4.81 (1.20–11.58) |

<0.001 |

|

Age |

1.10 (1.05–1.15) |

<0.001 |

References

- 1. Levy AR, Mayo NE, Grimard G. Re: “Heterogeneity of hip fracture: age, race, sex, and geographic patterns of femoral neck and trochanteric fractures among the US elderly”. Am J Epidemiol 1996;144:801-3.Article

- 2. Thorngren KG, Hommel A, Norrman PO, Thorngren J, Wingstrand H. Epidemiology of femoral neck fractures. Injury 2002;33 Suppl 3:C1-7.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Sing CW, Lin TC, Bartholomew S, et al. Global epidemiology of hip fractures: secular trends in incidence rate, post-fracture treatment, and all-cause mortality. J Bone Miner Res 2023;38:1064-75.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Viganò M, Pennestrì F, Listorti E, Banfi G. Proximal hip fractures in 71,920 elderly patients: incidence, epidemiology, mortality and costs from a retrospective observational study. BMC Public Health 2023;23:1963.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Cumming RG, Klineberg RJ. Fall frequency and characteristics and the risk of hip fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:774-8.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Parkkari J, Kannus P, Palvanen M, et al. Majority of hip fractures occur as a result of a fall and impact on the greater trochanter of the femur: a prospective controlled hip fracture study with 206 consecutive patients. Calcif Tissue Int 1999;65:183-7.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2005;16 Suppl 2:S3-7.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Schwarze M, Schiltenwolf M. Osteoporosis in the context of medial expert evidence. Z Orthop Unfall 2020;158:517-23.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Van Rietbergen B, Huiskes R, Eckstein F, Rüegsegger P. Trabecular bone tissue strains in the healthy and osteoporotic human femur. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:1781-8.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Walker MD, Shane E. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1979-91.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Bot RB, Chirla R, Hozan CT, Cavalu S. Mapping the spatial evolution of proximal femur osteoporosis: a retrospective cross-sectional study based on CT scans. Int J Gen Med 2024;17:1085-100.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Feng C, Zhang K, Zhan S, Gan Y, Xiang X, Niu W. Mechanical impact of regional structural deterioration and tissue-level compensation on proximal femur trabecular bone. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024;12:1448708.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Gustafsson A, Wallin M, Isaksson H. The influence of microstructure on crack propagation in cortical bone at the mesoscale. J Biomech 2020;112:110020.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Nalla RK, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Mechanistic fracture criteria for the failure of human cortical bone. Nat Mater 2003;2:164-8.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Taylor D, Hazenberg JG, Lee TC. Living with cracks: damage and repair in human bone. Nat Mater 2007;6:263-8.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 16. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 2001;285:785-95.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet 2002;359:1929-36.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Bergstrom U, Bjornstig U, Stenlund H, Jonsson H, Svensson O. Fracture mechanisms and fracture pattern in men and women aged 50 years and older: a study of a 12-year population-based injury register, Umeå, Sweden. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:1267-73.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245-51.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Collinge CA, Mir H, Reddix R. Fracture morphology of high shear angle “vertical” femoral neck fractures in young adult patients. J Orthop Trauma 2014;28:270-5.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Kong GM, Kwak JM, Jung GH. Eliminating projection error of measuring Pauwels’ angle in the femur neck fractures by CT plane manipulation. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2020;106:607-11.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Hey HW, Sng WJ, Lim JL, et al. Interpretation of hip fracture patterns using areal bone mineral density in the proximal femur. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015;135:1647-53.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 23. Kanis JA, Melton LJ, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 1994;9:1137-41.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Christie J. Hip fractures in adults younger than 50 years of age: epidemiology and results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995;(312):238-46.

- 25. Rikkonen T, Sund R, Sirola J, Honkanen R, Poole KES, Kröger H. Obesity is associated with early hip fracture risk in postmenopausal women: a 25-year follow-up. Osteoporos Int 2021;32:769-77.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Johansson H, Kanis JA, Odén A, et al. A meta-analysis of the association of fracture risk and body mass index in women. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:223-33.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Zheng R, Byberg L, Larsson SC, Höijer J, Baron JA, Michaëlsson K. Prior loss of body mass index, low body mass index, and central obesity independently contribute to higher rates of fractures in elderly women and men. J Bone Miner Res 2021;36:1288-99.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Mortensen SJ, Beeram I, Florance J, et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors associated with fragility hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Metab 2021;39:893-902.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 29. Xu C, Li H, Zhang C, et al. Quantitative analysis of primary compressive trabeculae distribution in the proximal femur of the elderly. Orthop Surg 2024;16:2030-9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Mahapatra B, Pal B. Biomechanical analysis of various internal fracture fixation devices used for treating femoral neck fractures: a comparative finite element analysis. Injury 2024;55:111717.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Wang F, Liu Y, Huo Y, et al. Biomechanical study of internal fixation methods for femoral neck fractures based on Pauwels angle. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023;11:1143575.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Thirunthaiyan MR, Mukherjee K, Prashanth T, Kumar DR. Predicting the anatomical location of neck of femur fractures in osteoporotic geriatric Indian population. Malays Orthop J 2022;16:103-11.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Heetveld MJ, Raaymakers EL, van Eck-Smit BL, van Walsum AD, Luitse JS. Internal fixation for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. Does bone density affect clinical outcome? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:367-73.ArticlePubMed

- 34. Zhao C, Li X, Liu P, et al. Predicting fracture classification and prognosis with Hounsfield units and femoral cortical index: a simple and cost-effective approach. J Orthop Sci 2024;29:1274-9.ArticlePubMed

- 35. Dhibar DP, Gogate Y, Aggarwal S, Garg S, Bhansali A, Bhadada SK. Predictors and outcome of fragility hip fracture: a prospective study from North India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2019;23:282-8.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 36. Bartels S, Gjertsen JE, Frihagen F, Rogmark C, Utvåg SE. Low bone density and high morbidity in patients between 55 and 70 years with displaced femoral neck fractures: a case-control study of 50 patients vs 150 normal controls. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:371.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 37. Yang R, Tsai K, Chieng P, Liu T. Symmetry of bone mineral density at the proximal femur with emphasis on the effect of side dominance. Calcif Tissue Int 1997;61:189-91.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 38. Mounach A, Rezqi A, Ghozlani I, Achemlal L, Bezza A, El Maghraoui A. Prevalence and risk factors of discordance between left- and right-hip bone mineral density using DXA. ISRN Rheumatol 2012;2012:617535.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 39. Lilley J, Walters BG, Heath DA, Drolc Z. Comparison and investigation of bone mineral density in opposing femora by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Osteoporos Int 1992;2:274-8.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 40. Yoon BH, Park JW, Lee CW, Koh YD. Different pattern of T-score discordance between patients with atypical femoral fracture and femur neck fracture. J Bone Metab 2023;30:87-92.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

, Yong-Uk Kwon

, Yong-Uk Kwon , Ji-Hun Park

, Ji-Hun Park

E-submission

E-submission KOTA

KOTA TOTA

TOTA TOTS

TOTS

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite