Abstract

Various complications can occur after hand fractures. Among them, joint stiffness and malunion are the most common and significant complications, which are often accompanied by tendon adhesions and joint contracture. Careful evaluations of injury characteristics, such as fracture patterns, alignment, and soft tissue injury, are the first step to select appropriate management strategies and prevent complications of hand fractures. Close observation of its clinical prognosis is also essential for early detection and preemptive management of complications. Management of complications includes immobilization, rehabilitation, and various surgical techniques such as tenolysis or capsular release for joint stiffness, corrective osteotomy for malunion, and revisional fixation with bone graft for nonunion. The authors discuss prevention, early recognition, and management strategies for complications of hand fractures in this review.

-

Keywords: Hand injuries, Complications, Malunited fractures, Complex regional pain syndrome, Rehabilitation

Introduction

Hand fractures, which include fractures of the metacarpal bones, proximal phalangeal bones, and distal phalangeal bones, are common fractures accounting for approximately 40% of upper extremity fractures [

1]. The hand has a complex anatomical structure with many structures in a small space, making it prone to frequent complications regardless of the surgeon's ability or treatment method [

2]. The complications that can occur in hand fractures include stiffness, malunion, deformity, nonunion, posttraumatic arthritis, infection, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS; historically termed reflex sympathetic dystrophy), and nerve and vascular damage (

Table 1) [

2]. While the frequency of complications is higher in open fractures compared to closed fractures and in comminuted fractures compared to simple fractures, it is important to understand that complications can still occur in simple closed fractures [

2,

3].

Conservative treatment of hand fractures typically requires 3–4 weeks of splint immobilization, and there is the risk of inducing hand stiffness, malunion, and deformity during immobilization [

2,

4,

5]. In contrast, surgical treatment allows for early finger movement after rigid fixation, which reduces the risk of hand stiffness, malunion, and deformity [

2,

6]. Surgical treatment is better for achieving good hand function but can also result in complications such as infection, hardware irritation, and nonunion [

2,

5,

6]. The treatment of complications is challenging to manage, and complications often cause unsatisfactory outcomes [

2,

6]. To achieve satisfactory treatment outcomes, it is important to recognize and prevent complications during treatment. The authors intended to discuss the treatment and prevention methods for the common complications, such as stiffness, malunion, deformity, nonunion, arthritis, infection, and chronic pain associated with hand fractures with a literature review in this article.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of their images in this review.

Stiffness

Stiffness is the most common complication during the treatment of hand fractures and one of the most challenging complications to treat [

2]. The risk of stiffness is higher in cases of severe comminuted fractures, open fractures, or crush injuries with extensive soft tissue damage around the fracture site (

Fig. 1) [

3]. Especially, proximal phalangeal fractures have a higher risk of stiffness compared to other hand fractures, so immobilization with a splint for more than 4 weeks can potentially cause stiffness [

2]. Therefore, the key principle is to achieve sufficient stability to permit early protected active motion; rigid internal fixation is one way to accomplish this, but selected stable fracture patterns can also be managed nonoperatively with functional support while still allowing early mobilization [

4,

7-

9]. In particular, uncomplicated fifth metacarpal neck fractures and selected metacarpal shaft fractures without rotational deformity or unacceptable shortening/angulation can often be treated functionally (e.g., buddy taping/soft wrap) with early protected mobilization, achieving outcomes comparable to more restrictive immobilization in appropriate patients [

7-

9]. A common mistake orthopedic surgeons make in treating hand fractures is unnecessarily prolonging rigid splint immobilization solely to observe radiographic callus formation. Phalangeal fractures typically heal within 4 weeks, but callus formation may not be visible on plain radiographs at that time [

2]. Therefore, rather than continuing rigid immobilization, gentle active motion exercises of the joints can be carefully initiated if there is no focal tenderness or pain at the fracture site on physical examination at approximately 4 weeks [

2]. If there are concerns about loss of reduction because radiographic healing appears insufficient, using a removable splint during active joint exercises and wearing the splint during other activities can be a practical alternative to prolonged rigid immobilization [

2]. Early joint motion is essential, especially in hand crush injuries [

4]. When a crush injury occurs to the hand, it damages all structures from the skin to the bone, causing severe swelling and stiffness of the soft tissues [

3]. Therefore, early joint motion helps minimize swelling and soft tissue stiffness, but rigid fracture fixation is necessary to allow early motion [

3].

Rigid internal fixation of fractures using plates allows early active joint motion, which can prevent hand stiffness, malunion, nonunion, and finger deformities [

3]. However, there are disadvantages, such as the risk of tendon injury, nerve damage, and infection from surgical treatment [

5]. Even with plate fixation, complications like finger stiffness or deformity can still occur if the fixation is not rigid enough to allow early joint motion or if the reduction is inadequate and finger alignment is incorrect [

5,

10].

Recently, intramedullary headless compression screw fixation has become popular as a minimally invasive surgical technique for extraarticular metacarpal and phalangeal fractures to provide stable fixation with minimal soft tissue dissection and extensor tendon irritation [

11]. This technique may enable early active movement and reduce stiffness and adhesions [

11]. In a recent meta-analysis, intramedullary screw fixation for metacarpal fractures had better patient-reported outcomes and a lower revisional surgery rate than K-wire fixation and plate fixation [

12,

13]. Nevertheless, the intramedullary screw fixation is only indicated in a particular fracture pattern without rotational instability and intraarticular involvement. Surgeons should know that this technique can also induce complications such as screw prominence/irritation, loss of reduction, and early arthrosis [

11,

14,

15].

Percutaneous K-wire fixation is less invasive and a commonly performed simple technique to minimize new soft tissue damage. However, it has potential problems with infection and loss of fracture fixation that can lead to finger deformity, nonunion, malunion, stiffness, and decreased function [

2,

16]. Additionally, in elderly patients with poor bone quality, the fixation strength of K-wires may be weaker compared to younger patients [

4,

17]. For comminuted or unstable fractures, K-wires alone may not maintain fracture reduction [

6]. K-wire fixation near joints can irritate soft tissues and prevent early joint motion [

18]. Therefore, this technique is suitable for young adult patients with good bone quality [

18]. However, percutaneous pinning can be performed even in elderly patients' fractures if it is stable without comminution and K-wire fixation alone is expected to provide sufficient stability for 4 weeks until union [

16].

To minimize pin-related complications, postoperative care and rehabilitation should be individualized according to fracture stability and the configuration of the pins. While the K-wires are in place, early protected motion of nonimmobilized joints should be encouraged as pain and swelling permit, using a removable splint when needed to balance protection and mobilization [

2]. Pin-site care protocols vary across institutions, and the choice of buried versus exposed wires should be individualized. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of hand and forearm fractures, buried K-wires were associated with a lower risk of pin-site infection compared with exposed wires, although the time to pin removal tended to be longer [

13]. Meticulous aseptic insertion technique, standardized pin-site care with clear patient education regarding early signs of infection, and timely clinical follow-up remain key determinants of infection risk [

15]. Radiographs are commonly obtained at 1–2-week intervals to confirm maintenance of reduction and to monitor healing progression. If there is no focal tenderness at the fracture site at approximately 4 weeks despite limited radiographic callus, the fracture may be considered clinically united [

16]. In that setting, the K-wires can be removed, and active finger exercises can be advanced to prevent joint stiffness and minimize ongoing pin-related problems [

16].

Treatment of finger stiffness is challenging. The first step in the treatment of finger stiffness is identifying the cause of the stiffness; physical examination is very important for determining the cause [

2,

17,

19]. On physical examination, if there is stiffness with both active and passive motion of the finger, it indicates joint capsule contracture [

2,

17,

19]. If there is stiffness only with active motion but not passive motion, it indicates adhesion of tendons to the fracture site soft tissues, joint capsule, bone, or hardware [

2]. Initial treatment of stiffness is aggressive finger exercise rehabilitation to maximize range of motion, and many patients recover sufficient motion for activities of daily living [

2]. However, if more than 3 months have passed since the fracture, recovery of joint motion cannot be expected with rehabilitation alone, and surgical treatment is necessary [

20]. Before surgical treatment for joint stiffness, plain radiographs should confirm that the fracture has healed with sufficient strength and intensive joint rehabilitation should be performed postoperatively [

20].

The surgical technique for finger joint contracture release varies depending on the location and severity of the stiffness [

3,

17]. For example, in cases of flexion contracture of the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP), surgical procedures are sequentially performed, including skin incision, adhesiolysis of finger flexor tendons, and release of the volar plate and volar portions of the collateral ligaments [

3,

17]. The same technique is used for flexion contracture of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) for MCP flexion contracture. Still, there are differences in the specific techniques for extension contracture of the MCP and PIP joints (

Table 2) [

2,

6]. Previous reports have stated that surgical treatment of finger stiffness can recover up to 70° of joint range of motion [

2,

21]. However, complete recovery is not possible, so many cases are still unsatisfactory even after surgery [

2,

21]. Therefore, prevention of finger stiffness through early joint motion can be considered the best treatment.

Malunion

Malunion is a united fracture that has healed in an abnormal alignment [

22]. All malunions always need to be treated, but treatment is necessary if this abnormal alignment causes impaired hand function [

23]. Finger malunions can be classified into intraarticular and extraarticular malunions [

24]. Intraarticular malunions greater than 1 mm can lead to posttraumatic arthritis [

22]. Furthermore, severe malunions can cause finger deformities, resulting in significant functional impairment [

2]. Although articular cartilage damage at the time of injury cannot be healed, joint surface incongruence that is severe enough to cause finger deformity or posttraumatic arthritis should be surgically corrected [

2]. Surgical correction should be performed before the complete fracture union because correction becomes much more difficult after the union. Treatment options for intraarticular malunions depend on the degree of finger deformity, type of injured joint, and presence of arthropathy [

2]. Surgical methods include corrective osteotomy, arthroplasty, and arthrodesis [

4,

24]. If intraarticular fractures have completely malunited, extraarticular corrective osteotomy can be used to realign the finger because direct correction is technically difficult [

4,

24].

Extraarticular malunion is the abnormal alignment of healed fractures outside the joint [

4,

24]. While extraarticular malunions are generally easier to treat than intraarticular malunions, corrective osteotomy should be performed if finger deformity is severe enough to cause impairment of normal joint function [

25]. According to Freeland et al. [

26] corrective osteotomy is commonly indicated for extraarticular malunions in the following cases:

(1) Angular deformity >15° in the middle and proximal phalanges; (2) articular incongruity; (3) angular deformity >10° in the index and middle metacarpal bones; (4) angular deformity >20° in the ring finger metacarpal bone; (5) angular deformity >30° in the little finger metacarpal bone; (6) rotational malunion >10° in the metacarpal bone (

Fig. 2).

The index and middle fingers have limited carpometacarpal joint (CMC) motion compared to other digits, so they have a smaller acceptable range for angular deformity and may require surgical correction even for minor angulation. In contrast, the ring and little finger have greater mobility at the fourth and fifth CMC and can tolerate up to 30° of metacarpal angulation without functional impairment [

26]. For shortened malunions of >2 mm in metacarpal bone, each 2 mm of shortening causes 7° of extension lag and decreased flexion strength at the MCP [

26]. Therefore, lengthening osteotomy is needed. Angular malunion of the proximal phalanx has an effect similar to shortening malunion [

27]. Angular deformity >15° causes functional impairment, and shortening >1 mm of the proximal phalanx leads to extension lag at the PIP. In those cases, corrective osteotomy should be performed [

27].

Metacarpal malunions typically present with a dorsal angulation due to the deforming forces of intrinsic and extrinsic flexor muscles [

25,

28]. Rotational forces may also be present, which can be evaluated with the fingers in a flexed position [

4,

25]. Shortening can occur in oblique and comminuted metacarpal fractures [

4,

25]. While up to 6 mm of shortening can be tolerated due to compensatory hyperextension of the MCP joint, each additional 2 mm of shortening results in 7° of extension lag [

4,

6,

25]. Shortening also reduces strength, with 2 mm of shortening causing an 8% loss of strength, and 10 mm of shortening resulting in a 45% reduction in grip strength [

2]. While exact guidelines vary, angular deformities of up to 10° in the index and middle fingers and up to 20° and 30° in the ring and little fingers can be tolerated, respectively [

2].

Osteotomies can be performed at the fracture site or at a distance from the fracture [

2]. The advantages of performing the osteotomy at the fracture site include restoring normal anatomy without creating a zigzag deformity, allowing access to soft tissues for tenolysis and capsulectomy, and correcting multiple deformities [

25,

28]. Therefore, osteotomy should be performed at the fracture site whenever possible [

25,

28]. Both open and closed wedge osteotomies can be performed for angular deformities [

27]. Closed wedge osteotomies are easier and more reliable, but shorten the metacarpal bone [

27]. Open wedge osteotomies can be used when shortening also needs correction, and cancellous bone grafting alone is sufficient if fixation is rigid [

27]. K-wires can also be used for stabilization, but plates and screws are preferred to allow early motion in open wedge osteotomies [

27].

Rotational malunions can cause finger overlap and are less tolerated as adjacent joints cannot compensate for the deformity [

25]. As little as 5° of rotational malunion can cause 1.5cm of finger overlap [

2]. Rotational osteotomies can be performed at the fracture site or at the proximal base as described by Weckesser [

29], allowing correction of up to 18° for the index, middle, and ring metacarpal bones and up to 30° for the little finger metacarpal bone. In cases with significant angular deformity, the osteotomy at the fracture site is a better surgical technique for simultaneously correcting both rotational and angular deformities [

25]. Another excellent option for rotational deformities is the proximal step-cut osteotomy first described by Manktelow et al. [

30], which allows for greater bone contact area and fixation with lag screws without the use of bulky plates. Fixation can be performed with K-wires or plates and screws. Many studies have been published on the results with high healing rates, deformity correction, and patient satisfaction of correction of rotational malunions with the above techniques.

Phalangeal malunions can also present with coronal and sagittal plane angular, rotational, and shortening deformity, similar to metacarpal malunions. Proximal phalangeal malunions characteristically show a volar angulation due to the flexion of the proximal fragment by the interossei and extension of the distal fragment by the central slip of the extensor tendon [

22,

23,

31]. Biomechanically, the dorsal surface of the bone becomes relatively shorter compared to the extensor tendon length when the volar angulation exceeds 15° [

22]. That results in about 12° of extension lag for every 1 mm shortening. When the angle exceeds 25°, both flexion and extension are impaired [

22]. The tendency for extension lag and stiffness in the PIP joint can quickly lead to fixed flexion contractures [

22].

Middle phalangeal malunions present with a dorsal angulation if the fracture is proximal to the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon (FDS) insertion and a volar angulation if distal to the FDS insertion [

27]. Volar angulation is more common and can significantly affect flexor tendon biomechanics [

27]. Phalangeal osteotomy at the fracture site is better than at other phalangeal sites or the metacarpal level [

22]. This allows simultaneous tenolysis and fixing of the other causes of deformity. However, performing osteotomy at the base of the proximal phalanx rather than near the PIP joint may be considered to reduce the risk of contracture [

22]. A closed wedge osteotomy using the dorsal periosteum as a hinge is a good option for volar malunions [

22]. This maintains bone length relative to the extensor tendon and allows good apposition of bone ends during healing [

2]. A lateral plate can then be applied apart from the tendons to reduce adhesions and allow early motion. For severely angulated malunions where the bone is significantly shortened relative to the tendons, a dorsal opening wedge osteotomy with a dorsal plate fixation should be performed [

31]. This theoretically restores the original bone length but causes a higher risk of adhesion formation and stiffness [

31]. Coronal plane malunions are often due to bone loss on the fracture site [

31]. Good results have been shown with an opening wedge osteotomy, bone grafting, and lateral plate fixation while preserving the cortex on the apex side. Rotational deformities may be combined with angular deformities and shortening and corrected simultaneously [

2]. Buchler et al. [

32] reported 100% union rates and deformity correction of phalangeal malunions, but 50% of cases required simultaneous tenolysis and/or capsulectomy due to the high incidence of tendon adhesions and joint contractures. Trumble and Gilbert [

33] recommended in situ osteotomy of the phalanx at the fracture site rather than the metacarpal bone because simultaneous tenolysis and capsulotomy could be performed in most cases. All of their patients healed and had complete correction of deformity, with improvements of 15° in PIP joint motion and 10° in distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) motion [

2]. Therefore, treatment of phalangeal malunions is more challenging than metacarpal malunions due to the surrounding intrinsic apparatus and extrinsic tendons, the tendency for tendon adhesions, and the development of PIP joint contractures. Surgical treatment can significantly improve hand function and patient satisfaction [

2].

Nonunion

Nonunion is a relatively rare complication in hand fractures due to the rich blood supply, but it can occur commonly in complex injuries such as open fractures with associated nerve, vascular, and tendon injuries, or crush injuries [

28]. They are also surgical complications resulting from the disruption of microvascular blood supply around the bone during open reduction or inadequate fracture reduction with a wide fracture gap [

23]. Most nonunions in hand fractures are atrophic nonunions, often associated with bone loss or infection [

28]. When atrophic nonunion occurs, the nonunited bone should be debrided and treated with rigid internal fixation and autologous bone grafting harvested from sites like the distal radius or olecranon [

28]. Hypertrophic nonunion after hand fractures is rare but can be easily treated with more rigid internal fixation alone [

28].

Diagnosing nonunion in hand fractures can be challenging, as radiolucent lines may be visible on plain radiographs for up to a year after fracture [

2]. However, if there are no clinical symptoms such as pain at the fracture site, the fracture can be considered united. Therefore, other factors such as pain, instability, deformity, and fixation failure should be considered when diagnosing fracture nonunion along with plain radiographs [

2]. To avoid the risk of finger joint stiffness, fracture sites should not be immobilized for more than 6 weeks, even if the union is delayed [

6]. If both nonunion and joint stiffness exist, the joint should be released simultaneously with surgical treatment of the nonunion [

6].

In many cases of nonunion, salvage procedures such as arthrodesis or amputation may be necessary to treat associated injuries [

23]. Conservative treatments like bone stimulators have not been proven effective to date [

23]. Nonunion of the distal phalangeal shaft is relatively common and can be treated with compression screws alone or with bone grafting if the fracture is atrophic [

34]. Autologous grafting is the standard technique for nonunion treatment, and cancellous autografts are generally sufficient to stimulate healing [

34]. Structural autografts can be used for significant bone defects in the load-sharing portion [

34]. Cancellous autograft chips can be compressed in a syringe to create a semistructural bone peg, which may be suitable for most hand fractures [

2]. Technically, all atrophic and nonviable bone should be debrided until bone bleeding is visible [

23]. Implants used for internal fixation in the nonunion should be slightly larger than those typically used for acute fractures to provide additional mechanical stability [

23]. Few studies have reported on outcomes after surgical management of nonunions with internal fixation and bone grafting, and the results are not satisfactory [

20,

23,

27,

28,

35-

37]. Harness et al. [

38] reported that, among 25 patients with nonunion (including 15 complex hand injuries), few fingers achieved good function; however, plate-and-screw fixation provided better stability than K-wire fixation. The authors’ experience was similar (

Fig. 3).

Due to the limited success rate of nonunion reconstruction through bone grafting and revisional internal fixation, arthrodesis and amputation play important roles in the surgical treatment of nonunions [

27]. Arthrodesis is suitable for intraarticular and periarticular nonunions with severe joint stiffness [

27]. Amputation is indicated for nonunion with significant bone loss, chronic infection, permanent sensory loss, and poor soft tissue coverage [

27]. Stiff fingers often inhibit hand function, and the nonunited stiff finger also requires protection and causes stiffness in adjacent fingers [

17]. Therefore, amputation is a good solution for these patients and almost always improves their function [

17,

27].

Arthritis

Posttraumatic arthritis can result from intraarticular malunion or cartilage damage [

27]. While cartilage damage may be irreversible, joint incongruity can be surgically corrected and is much easier to correct at the acute state [

27]. Treating established intraarticular malunions can be very challenging. Treatment options depend on the patient, deformity, involved joint, and presence of arthropathy, and may include osteotomy, various types of arthroplasty, and arthrodesis [

2,

6].

There are two general techniques to correct intraarticular malunions: For malunions less than 8–10 weeks old where the old fracture line is still definable, an osteotomy through the fracture can reverse the deformity and improve articular congruence [

27]. However, this requires manipulating and fixing small, unstable articular fragments, which theoretically risks biological breakdown and fixation failure [

31,

38]. For chronic malunions where the fracture line is no longer visible, special osteotomy techniques are needed to reduce the articular surface [

38]. Teoh et al. [

39] described a technique of wedge osteotomy in the intercondylar region to create a larger condylar fragment. This allows easier correction of articular malunion and fixation of a larger fragment [

39]. It theoretically reduces risks of fixation failure, nonunion, and osteonecrosis [

39]. A supracondylar closing wedge osteotomy just proximal to the collateral ligament insertion has also been described with good results [

2,

31,

40]. For the most severe deformities with arthropathy, arthrodesis and arthroplasty are excellent options [

23]. Bony mallet injuries can cause intraarticular malunions of the DIP joint [

41]. The main concern with these injuries is the extension lag of the DIP joint and consequent hyperextension of the PIP joint, resulting in a swan neck deformity [

41]. Incongruity can also induce DIP arthropathy. In those cases, arthrodesis in 5°–10° of flexion is most optimal in hand function [

41].

Malunions around the PIP can also be combined with stiffness and angular and rotational deformities [

25,

31]. Treatment options are extraarticular and intraarticular osteotomies, depending on the deformity, as described above. For dorsal PIP fracture-dislocations with volar articular surface loss of the middle phalanx, volar plate arthroplasty or hemihamate arthroplasty can be used [

25,

31]. While volar plate arthroplasty can have flexion contracture and recurrent instability, hemihamate arthroplasty is effective for up to 50% articular surface loss [

25,

31]. If the deformity cannot be reconstructed or arthropathy already exists around the index PIP, arthrodesis is the best treatment option to provide a stable base for pinch, while the remaining fingers can be treated with arthroplasty to preserve motion [

23,

42].

Malunions around the MCP occur less frequently but can be challenging to treat. Again, treatment options include intraarticular and extraarticular osteotomies [

40]. Arthrodesis and arthroplasty are suitable for severe, uncorrectable deformities with arthropathy [

40]. Arthrodesis of the index MCP may be a desirable option to provide stability of the MCP during pinch, like in the PIP, but the other MCP should be treated with arthroplasty [

22].

Infection

The infection rate in hand fractures is related to the severity of soft tissue damage and wound contamination [

27,

35]. Necrosis of surrounding soft tissues and periosteal stripping creates an environment vulnerable to infection [

27]. In open hand fractures, osteomyelitis can occur up to 11% after surgical treatment [

2,

43]. Some reports indicate that treatment of osteomyelitis in hand fractures is challenging, and the amputation rate is up to 40% [

2,

43]. The definitive diagnosis of osteomyelitis is possible only by bone culture [

2,

43]. Clinically, patients present with swelling, erythema, tenderness, limited motion, and sometimes draining sinuses [

20,

44,

45]. Fever is usually absent, but inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein are elevated. White blood cell counts may be normal or elevated. X-rays may show sequestrum and involucrum in chronic cases [

19,

34].

Acute osteomyelitis without abscess formation can be managed by intravenous antibiotics with monitoring clinical status and inflammatory markers, followed by a short course of oral antibiotics once inflammatory markers normalize [

19,

34]. Surgical treatment is necessary for chronic or acute osteomyelitis with an abscess. The surgical goals are to remove all infected and nonviable tissue, including bone, adequately stabilize the fracture, and provide sufficient soft tissue coverage [

32,

37]. Loosened hardware should be removed, and fractures should be stabilized with external fixation [

6,

20]. Also, hardware should be removed if the fracture has united. However, if the fracture has not yet united, hardware should not be removed until union with chronic suppressive antibiotics [

6,

20]. Dead space can be managed with antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers and external fixation. Flap coverage is helpful for soft tissue defects. Antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers can be used with external fixation to maintain length and alignment. Final reconstruction can be performed after the infection is completely cured [

3].

Chronic pain

The exact incidence of CRPS after hand fractures is unknown, but CRPS is recognized as a not-uncommon complication following upper extremity injuries [

46]. It has been reported after distal radius fractures and fasciectomy for Dupuytren disease [

28,

46-

48]. While it can also occur after hand fractures, there is limited information in the current literature regarding CRPS specifically following hand fractures [

28]. Clinically, CRPS presents with continuing pain disproportionate to the inciting event, often accompanied by sensory disturbance (allodynia/hyperalgesia), autonomic changes (temperature or color asymmetry), edema/sudomotor abnormalities, and motor/trophic changes that may ultimately impair function [

27,

28,

47,

48].

CRPS is primarily a clinical diagnosis without a definitive confirmatory test. Current recommendations support the use of the Budapest clinical criteria, which require disproportionate continuing pain, symptoms in at least three of four categories (sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/edema, motor/trophic), signs in at least two categories on examination, and the exclusion of alternative diagnoses that better explain the presentation [

49,

50]. In patients with disproportionate pain after treatment of a hand fracture, clinicians should also evaluate for other causes such as infection, malunion/nonunion, tendon adhesions, and discrete peripheral nerve pathology, as these may mimic or coexist with CRPS [

27,

47].

Cold hypersensitivity has been widely reported in the literature as a symptom of CRPS, but it remains poorly understood and challenging to treat [

27,

28,

47,

48]. CRPS can manifest as chronic pain, nonunion, stiffness, edema, atrophy, cold hypersensitivity, and radiographic osteopenia of the hand [

27,

28,

47,

48]. CRPS may also occur due to sympathetic hyperactivity without specific nerve damage or surgical nerve injury [

46]. Therefore, when symptoms follow a specific nerve distribution, diagnostic injections with local anesthetics may help identify neuromas or nerve compression [

47]. Ancillary tests may be used selectively to exclude alternative diagnoses or to support clinical suspicion; however, they should not delay management. In particular, three-phase bone scintigraphy has limited diagnostic utility for CRPS of the hand and may postpone timely rehabilitation or necessary surgical decision-making [

49,

51]. Sympathetic nerve blocks are not diagnostic, but may be considered as part of a multidisciplinary treatment strategy in selected patients when sympathetic features are prominent, to facilitate participation in rehabilitation [

49,

51].

Early recognition is the most important for the good prognosis of CRPS [

52]. The management goal of CRPS is functional restoration [

27,

47,

49]. Initial treatment includes antidepressants, anticonvulsants, calcium channel blockers, and adrenergic agents, along with hand therapy to prevent stiffness [

27,

47]. Opioids can also be used. Nevertheless, continuous rehabilitation is essential to maintain hand function, patients may not be cooperative with hand therapy due to severe pain [

27,

47]. Warm baths and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation devices may be helpful with pain control [

52]. Adjunctive noninvasive neurocognitive treatment, such as graded motor imagery and mirror therapy, may also facilitate pain reduction and functional recovery [

49].

Surgical intervention should not be considered for CRPS itself. However, specific procedures, such as neurolysis, nerve decompression, or neuroma excision, may be appropriate only for specific peripheral nerve pathology [

47,

49]. For patients with refractory systemic sympathetic hyperactivity, sympathectomy may be helpful in certain cases [

47].

Conclusions

Complications can occur in hand fractures regardless of the treatment method and severity of injury. If complications occur, their treatment is challenging, and the treatment outcomes also can be poor. Since prevention of complications is the best way to achieve good treatment outcomes, orthopedic surgeons should possess profound knowledge and experience regarding the causes of complications and pay attention to avoiding complications in hand fractures.

Article Information

-

Author contributions

All the work was done by Jong Woo Kang.

-

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Not applicable.

-

Acknowledgments

This review article is an expanded and updated version of the author's previous work, which was published in the Journal of the Korean Fracture Society 2024;37:46–51.

-

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.(A) A case with multiple open hand fracture-dislocations and severe soft tissue injury. (B) Preoperative plain radiograph shows multiple hand and wrist fractures and dislocations. (C) A postoperative plain radiograph shows that temporary K-wire fixation was performed to maintain bony alignment and manage soft tissue injury. (D) The last follow-up photograph shows severe finger stiffness and permanent disability.

Fig. 2.(A) A case with rotational malunion of the fifth metacarpal bone that induces finger scissoring and disability. (B) Finger scissoring can be corrected by derotational osteotomy.

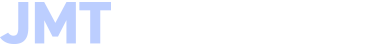

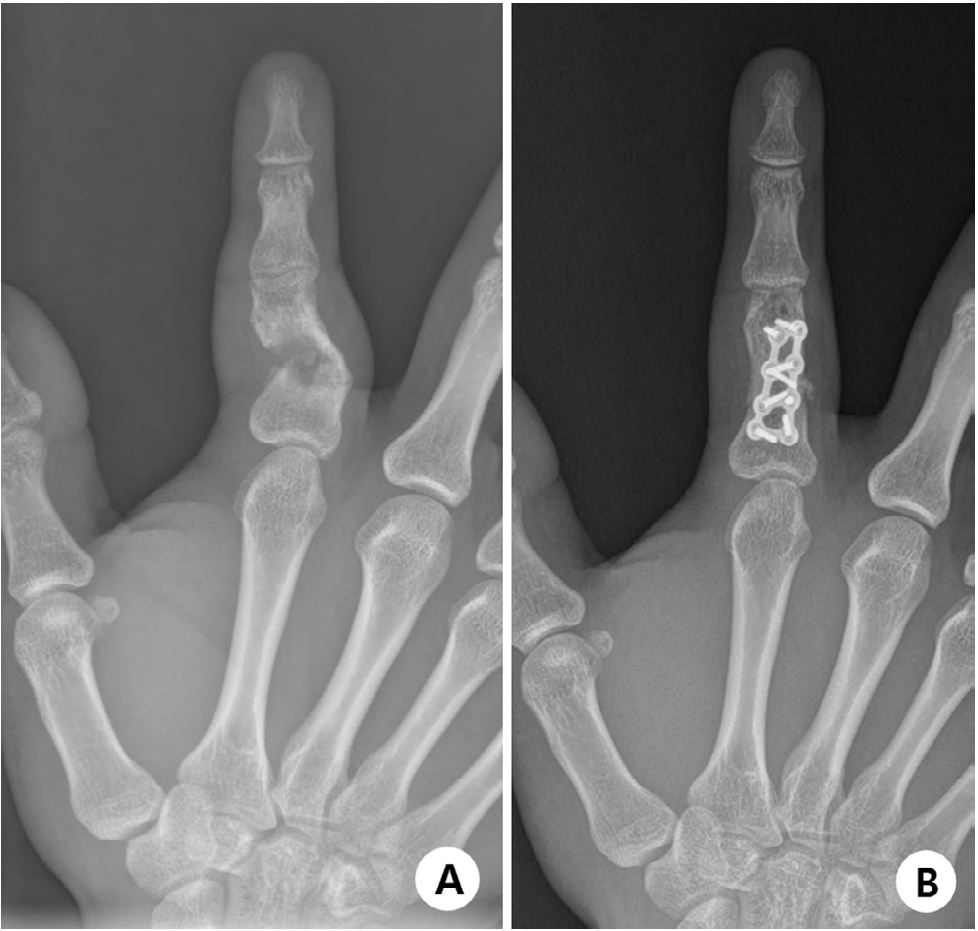

Fig. 3.(A) A case with atrophic nonunion and consequent reduction loss. (B) Atrophic nonunion can be treated surgically by stable fixation and autogenous cancellous bone graft.

Table 1.Complications of hand fractures

|

Affected structure |

Complication |

|

Bone |

Nonunion, malunions, delayed union, avascular necrosis, osteomyelitis, amputation |

|

Soft tissue |

Stiffness/motion loss, instability, laxity, poor durability, lack of coverage, contracture, flexion/extension loss |

|

Tendon |

Adhesions, lag, tightness |

|

Nerve |

Numbness, hypersensitivity, complex regional pain syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) |

|

Vessel |

Ischemia, congestion |

|

Others |

Vibration and temperature sensitivity, chondrolysis, acute pain, joint laxity |

Table 2.Recommended surgical procedures to release hand joint stiffness

|

Affected joint and conditions |

Sequence of procedures |

|

MCP stiff in extension |

Release (1) skin and extensor from capsule, (2) dorsal capsule, (3) articular surface and volar pouch, (4) dorsal half of collateral ligaments |

|

MCP stiff in flexion |

Release (1) skin, (2) adhesions of long flexors, (3) volar plate, (4) volar half of collateral ligaments |

|

PIP stiff in extension |

Release (1) skin, (2) extensor from capsule (preserve central slip), (3) dorsal capsule, (4) dorsal third to half of collateral ligaments |

|

PIP stiff in flexion |

Release (1) skin, (2) retinacular ligaments, (3) adhesions of long flexors, (4) volar half of collateral ligaments, (5) volar plate |

References

- 1. Alfort H, Von Kieseritzky J, Wilcke M. Finger fractures: epidemiology and treatment based on 21341 fractures from the Swedish Fracture register. PLoS One 2023;18:e0288506. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Markiewitz AD. Complications of hand fractures and their prevention. Hand Clin 2013;29:601-20.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Del Pinal F. An update on the management of severe crush injury to the forearm and hand. Clin Plast Surg 2020;47:461-89.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Boeckstyns ME. Current methods, outcomes and challenges for the treatment of hand fractures. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2020;45:547-59.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Baertl S, Alt V, Rupp M. Surgical enhancement of fracture healing: operative vs. nonoperative treatment. Injury 2021;52 Suppl 2:S12-7.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Meals C, Meals R. Hand fractures: a review of current treatment strategies. J Hand Surg Am 2013;38:1021-31.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Martínez-Catalán N, Pajares S, Llanos L, Mahillo I, Calvo E. A prospective randomized trial comparing the functional results of buddy taping versus closed reduction and cast immobilization in patients with fifth metacarpal neck fractures. J Hand Surg Am 2020;45:1134-40.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Mohamed MB, Paulsingh CN, Ahmed TH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of buddy taping versus reduction and casting for non-operative management of closed fifth metacarpal neck fractures. Cureus 2022;14:e28437. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Peyronson F, Ostwald CS, Edsfeldt S, Hailer NP, Giddins G, Muder D. Nonsurgical treatment versus surgical treatment in displaced metacarpal spiral fractures: extended 4.5-year follow-up of a previously randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am 2025;50:1190-7.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Guerrero EM, Baumgartner RE, Federer AE, Mithani SK, Ruch DS, Richard MJ. Complications of low-profile plate fixation of phalanx fractures. Hand (N Y) 2021;16:248-52.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Hug U, Fiumedinisi F, Pallaver A, et al. Intramedullary screw fixation of metacarpal and phalangeal fractures: a systematic review of 837 patients. Hand Surg Rehabil 2021;40:622-30.ArticlePubMed

- 12. DelPrete CR, Chao J, Varghese BB, Greenberg P, Iyer H, Shah A. Comparison of intramedullary screw fixation, plating, and k-wires for metacarpal fracture fixation: a meta-analysis. Hand (N Y) 2025;20:691-700.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Hidajat NN, Magetsari RM, Prasetiyo GT, Respati DR, Tjandra KC. Buried or exposed Kirschner wire for the management of hand and forearm fractures: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. PLoS One 2024;19:e0296149. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Anene CC, Thomas TL, Matzon JL, Jones CM. Complications following intramedullary screw fixation for metacarpal fractures: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am 2024;49:1043.Article

- 15. Levy KH, Sedaghatpour D, Avoricani A, Kurtzman JS, Koehler SM. Outcomes of an aseptic technique for Kirschner wire percutaneous pinning in the hand and wrist. Injury 2021;52:889-93.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Faruqui S, Stern PJ, Kiefhaber TR. Percutaneous pinning of fractures in the proximal third of the proximal phalanx: complications and outcomes. J Hand Surg Am 2012;37:1342-8.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Neumeister MW, Winters JN, Maduakolum E. Phalangeal and metacarpal fractures of the hand: preventing stiffness. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021;9:e3871. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 18. Balaram AK, Bednar MS. Complications after the fractures of metacarpal and phalanges. Hand Clin 2010;26:169-77.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Zuo KJ, Saggaf M, von Schroeder HP, Binhammer P. Outcomes of secondary combined proximal interphalangeal joint release and zone II flexor tenolysis. Hand (N Y) 2020;15:502-8.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 20. Hsu LP, Schwartz EG, Kalainov DM, Chen F, Makowiec RL. Complications of K-wire fixation in procedures involving the hand and wrist. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36:610-6.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Yamazaki H, Kato H, Uchiyama S, Ohmoto H, Minami A. Results of tenolysis for flexor tendon adhesion after phalangeal fracture. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2008;33:557-60.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Freeland AE, Lindley SG. Malunions of the finger metacarpals and phalanges. Hand Clin 2006;22:341-55.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Ring D. Malunion and nonunion of the metacarpals and phalanges. Instr Course Lect 2006;55:121-8.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Kang HJ, Kim JS. The current concepts in treatment of fracture-dislocations of the finger. J Korean Orthop Assoc 2020;55:457-71.ArticlePDF

- 25. Raducha JE, Hammert WC. Metacarpal and phalangeal malunions: is it all about the rotation. Hand Clin 2024;40:141-9.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Freeland AE, Orbay JL. Extraarticular hand fractures in adults: a review of new developments. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;445:133-45.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Gajendran VK, Gajendran VK, Malone KJ. Management of complications with hand fractures. Hand Clin 2015;31:165-77.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Wellborn PK, Allen AD, Draeger RW. Current outcomes and treatments of complex phalangeal and metacarpal fractures. Hand Clin 2023;39:251-63.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Weckesser EC. Rotational osteotomy of the metacarpal for overlapping fingers. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1965;47:751-6.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Manktelow RT, Mahoney JL. Step osteotomy: a precise rotation osteotomy to correct scissoring deformities of the fingers. Plast Reconstr Surg 1981;68:571-6.PubMed

- 31. Chen KJ, Huang YP, Lo IN, Huang YC. Corrective osteotomy for distal condylar malunion of the proximal phalanx in adolescents: comparison of K-wire and locking plate fixation. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2022;47:935-43.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 32. Büchler U, Gupta A, Ruf S. Corrective osteotomy for post-traumatic malunion of the phalanges in the hand. J Hand Surg Br 1996;21:33-42.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 33. Trumble T, Gilbert M. In situ osteotomy for extra-articular malunion of the proximal phalanx. J Hand Surg Am 1998;23:821-6.ArticlePubMed

- 34. Mortada H, AlNojaidi TF, Bhatt G, et al. Evaluating Kirschner wire fixation versus titanium plating and screws for unstable phalangeal fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of postoperative outcomes. J Hand Microsurg 2024;16:100055.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 35. Bannasch H, Heermann AK, Iblher N, Momeni A, Schulte-Mönting J, Stark GB. Ten years stable internal fixation of metacarpal and phalangeal hand fractures-risk factor and outcome analysis show no increase of complications in the treatment of open compared with closed fractures. J Trauma 2010;68:624-8.ArticlePubMed

- 36. Page SM, Stern PJ. Complications and range of motion following plate fixation of metacarpal and phalangeal fractures. J Hand Surg Am 1998;23:827-32.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Botte MJ, Davis JL, Rose BA, et al. Complications of smooth pin fixation of fractures and dislocations in the hand and wrist. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;(276):194-201.Article

- 38. Harness NG, Chen A, Jupiter JB. Extraarticular osteotomy for malunited unicondylar fractures of the proximal phalanx. J Hand Surg Am 2005;30:566-72.ArticlePubMed

- 39. Teoh LC, Yong FC, Chong KC. Condylar advancement osteotomy for correcting condylar malunion of the finger. J Hand Surg Br 2002;27:31-5.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 40. Gollamudi S, Jones WA. Corrective osteotomy of malunited fractures of phalanges and metacarpals. J Hand Surg Br 2000;25:439-41.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 41. Wang WC, Hsu CE, Yeh CW, Ho TY, Chiu YC. Functional outcomes and complications of hook plate for bony mallet finger: a retrospective case series study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:281.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 42. van der Lei B, de Jonge J, Robinson PH, Klasen HJ. Correction osteotomies of phalanges and metacarpals for rotational and angular malunion: a long-term follow-up and a review of the literature. J Trauma 1993;35:902-8.ArticlePubMed

- 43. Lester B, Mallik A. Impending malunions of the hand: treatment of subacute, malaligned fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;(327):55-62.

- 44. Duncan RW, Freeland AE, Jabaley ME, Meydrech EF. Open hand fractures: an analysis of the recovery of active motion and of complications. J Hand Surg Am 1993;18:387-94.ArticlePubMed

- 45. Kurzen P, Fusetti C, Bonaccio M, Nagy L. Complications after plate fixation of phalangeal fractures. J Trauma 2006;60:841-3.ArticlePubMed

- 46. Pendón G, Salas A, García M, Pereira D. Complex regional pain syndrome type 1: analysis of 108 patients. Reumatol Clin 2017;13:73-7.ArticlePubMed

- 47. Pfister M, Fischer L. The treatment of the Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS 1 and CRPS 2) of the upper limb with repeated local anaesthesia to the stellate ganglion. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2009;98:247-57.ArticlePubMed

- 48. Boyacı A, Tutoğlu A, Boyacı FN, Yalçın Ş. Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 after fracture of distal phalanx: case report. Agri 2014;26:187-90.ArticlePubMed

- 49. Harden RN, McCabe CS, Goebel A, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 5th edition. Pain Med 2022;23:S1-53.ArticlePDF

- 50. Harden NR, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain 2010;150:268-74.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 51. Piñal FD, Lim JX, Williams DC, Ruas JS, Studer AT. Triphasic bone scintigraphy is not useful in diagnosis and may delay surgical treatment of CRPS of the hand. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol 2025;30:34-41.ArticlePubMed

- 52. Gutiérrez-Espinoza H, Zavala-González J, Gutiérrez-Monclus R, Araya-Quintanilla F. Functional outcomes after a physiotherapy program in elderly patients with complex regional pain syndrome type I after distal radius fracture: a prospective observational study. Hand (N Y) 2022;17:81S-86S.ArticlePubMedPDF

E-submission

E-submission KOTA

KOTA TOTA

TOTA TOTS

TOTS

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite