Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Musculoskelet Trauma > Volume 30(4); 2017 > Article

-

Review Article

- Malunion: Deformity Correction of the Upper Extremity

-

Soo-Min Cha, M.D., Ph.D.

, Hyun-Dae Shin, M.D., Ph.D.

, Hyun-Dae Shin, M.D., Ph.D.

-

Journal of the Korean Fracture Society 2017;30(4):209-218.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.12671/jkfs.2017.30.4.209

Published online: October 25, 2017

Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University School of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea.

- Correspondence to: Hyun-Dae Shin, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chungnam National University School of Medicine, 266 Munhwa-ro, Jung-gu, Daejeon 35015, Korea. Tel: +82-42-280-7349, Fax: +82-42-252-7098, hyunsd@cnu.ac.kr

Copyright © 2017 The Korean Fracture Society. All rights reserved.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 739 Views

- 18 Download

Abstract

- Malunions after fractures are classified as shortened, angulated, torsion, or rotational deformities that is outside the acceptable range, regardless of the location, whether upper or lower extremity. The distinct feature of a malunion in the upper extremity is that it is free from weight bearing; thus, some degree of shortening is allowed compared with the contralateral normal side in long bones, such as the humerus, radius, or ulna. However, malunions associated with functional impairment, especially angulated or rotational deformities, are more likely to develop instability, degenerative lesions, or rarely, compressive neuropathy. Hence, malunions with such association may occasionally require correction.

- 1. Cattaneo R, Catagni MA, Guerreschi F. Applications of the Ilizarov method in the humerus. Lengthenings and nonunions. Hand Clin, 1993;9:729-739.

- 2. Cattaneo R, Villa A, Catagni MA, Bell D. Lengthening of the humerus using the Ilizarov technique. Description of the method and report of 43 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1990;(250):117-124.

- 3. Paley D, Kelly D. Lengthening and deformity correction in the upper extremities. Atlas Hand Clin, 2000;5:117-172.

- 4. Davids JR, Lamoreaux DC, Brooker RC, Tanner SL, Westberry DE. Translation step-cut osteotomy for the treatment of post-traumatic cubitus varus. J Pediatr Orthop, 2011;31:353-365.Article

- 5. Eamsobhana P, Kaewpornsawan K. Double dome osteotomy for the treatment of cubitus varus in children. Int Orthop, 2013;37:641-646.ArticlePDF

- 6. Solfelt DA, Hill BW, Anderson CP, Cole PA. Supracondylar osteotomy for the treatment of cubitus varus in children: a systematic review. Bone Joint J, 2014;96-B:691-700.

- 7. Cha SM, Shin HD, Ahn JS. Relationship of cubitus varus and ulnar varus deformity in supracondylar humeral fractures according to the age at injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 2016;25:289-296.Article

- 8. Oppenheim WL, Clader TJ, Smith C, Bayer M. Supracondylar humeral osteotomy for traumatic childhood cubitus varus deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1984;(188):34-39.Article

- 9. Bellemore MC, Barrett IR, Middleton RW, Scougall JS, Whiteway DW. Supracondylar osteotomy of the humerus for correction of cubitus varus. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1984;66:566-572.ArticlePDF

- 10. Ahn SR, Shin HD, Rhee KJ, Lee JK, Jeong JT. Supracondylar quadrilateral displacement osteotomy for cubitus varus deformity: new operative technique. J Korean Orthop Assoc, 1998;33:326-334.ArticlePDF

- 11. Hui JH, Torode IP, Chatterjee A. Medial approach for corrective osteotomy of cubitus varus: a cosmetic incision. J Pediatr Orthop, 2004;24:477-481.

- 12. DeRosa GP, Graziano GP. A new osteotomy for cubitus varus. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1988;(236):160-165.Article

- 13. Moradi A, Vahedi E, Ebrahimzadeh MH. Surgical technique: spike translation: a new modification in step-cut osteotomy for cubitus varus deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2013;471:1564-1571.Article

- 14. Kumar K, Sharma VK, Sharma R, Maffulli N. Correction of cubitus varus by French or dome osteotomy: a comparative study. J Trauma, 2000;49:717-721.Article

- 15. Banerjee S, Sabui KK, Mondal J, Raj SJ, Pal DK. Corrective dome osteotomy using the paratricipital (triceps-sparing) approach for cubitus varus deformity in children. J Pediatr Orthop, 2012;32:385-393.Article

- 16. Bauer AS, Pham B, Lattanza LL. Surgical correction of cubitus varus. J Hand Surg Am, 2016;41:447-452.Article

- 17. Takeyasu Y, Oka K, Miyake J, Kataoka T, Moritomo H, Murase T. Preoperative, computer simulation-based, three-dimensional corrective osteotomy for cubitus varus deformity with use of a custom-designed surgical device. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2013;95:e173.Article

- 18. Zhang YZ, Lu S, Chen B, Zhao JM, Liu R, Pei GX. Application of computer-aided design osteotomy template for treatment of cubitus varus deformity in teenagers: a pilot study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 2011;20:51-56.Article

- 19. Takagi T, Takayama S, Nakamura T, Horiuchi Y, Toyama Y, Ikegami H. Supracondylar osteotomy of the humerus to correct cubitus varus: do both internal rotation and extension deformities need to be corrected? J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2010;92:1619-1626.Article

- 20. Morrey BF, Askew LJ, Chao EY. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1981;63:872-877.Article

- 21. Müller ME, Allgöwer M, Willenegger H. Technique of internal fixation of fractures. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1965.

- 22. Dumont CE, Thalmann R, Macy JC. The effect of rotational malunion of the radius and the ulna on supination and pronation. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2002;84:1070-1074.ArticlePDF

- 23. Sardelli M, Tashjian RZ, MacWilliams BA. Functional elbow range of motion for contemporary tasks. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2011;93:471-477.Article

- 24. Trousdale RT, Linscheid RL. Operative treatment of malunited fractures of the forearm. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1995;77:894-902.Article

- 25. Jayakumar P, Jupiter JB. Reconstruction of malunited diaphyseal fractures of the forearm. Hand (N Y), 2014;9:265-273.ArticlePDF

- 26. Jupiter JB, Fernandez DL, Levin LS, Wysocki RW. Reconstruction of posttraumatic disorders of the forearm. Instr Course Lect, 2010;59:283-293.Article

- 27. Margaliot Z, Haase SC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM, Chung KC. A meta-analysis of outcomes of external fixation versus plate osteosynthesis for unstable distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am, 2005;30:1185-1199.Article

- 28. Weckesser EC. Rotational osteotomy of the metacarpal for overlapping fingers. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1965;47:751-756.Article

- 29. Gross MS, Gelberman RH. Metacarpal rotational osteotomy. J Hand Surg Am, 1985;10:105-108.Article

REFERENCES

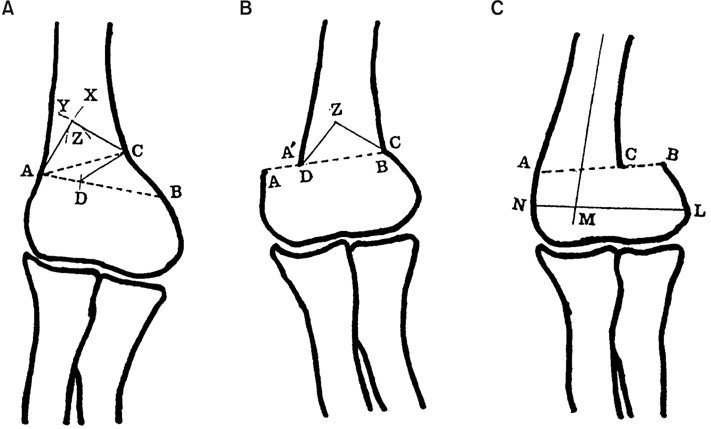

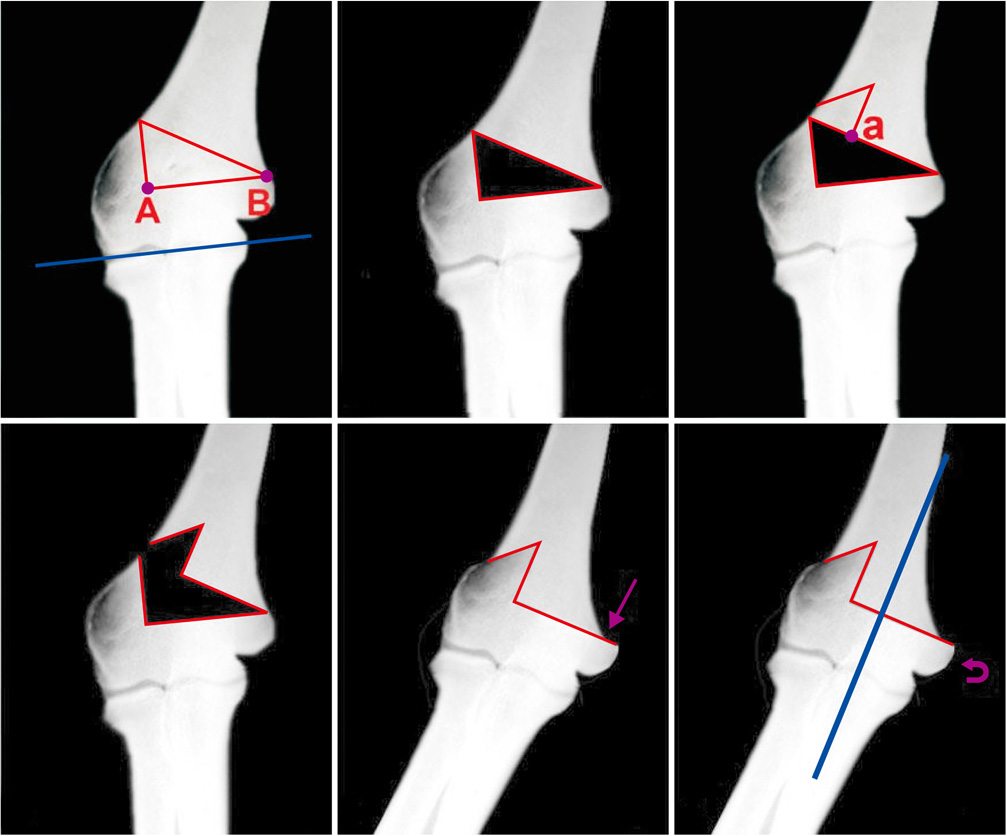

Fig. 2

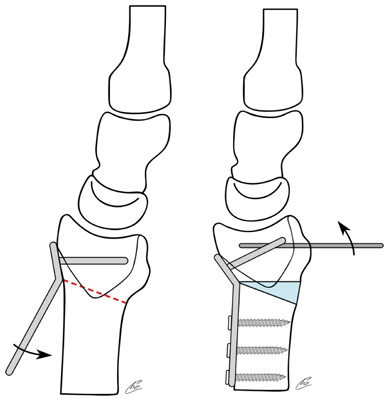

Schemati drawing of supracondylar quadrilateral displacement osteotomy. (A) ∠CAB: correction angle BC=CZ, DC=AZ, ΔAZC: DCB, □ZADC: being removed part. (B) After supracondylar quadrilateral displacement osteotomy, the distal fragment was medially displaced (AD distance) and wedge (AZC) was formed on line AC. (C) After French osteotomy (lateral closing wedge osteotomy), the prominence of lateral condyle becomes positive (author's method).

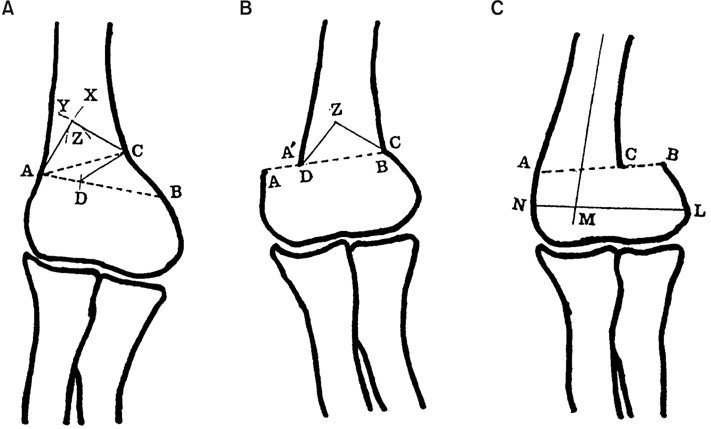

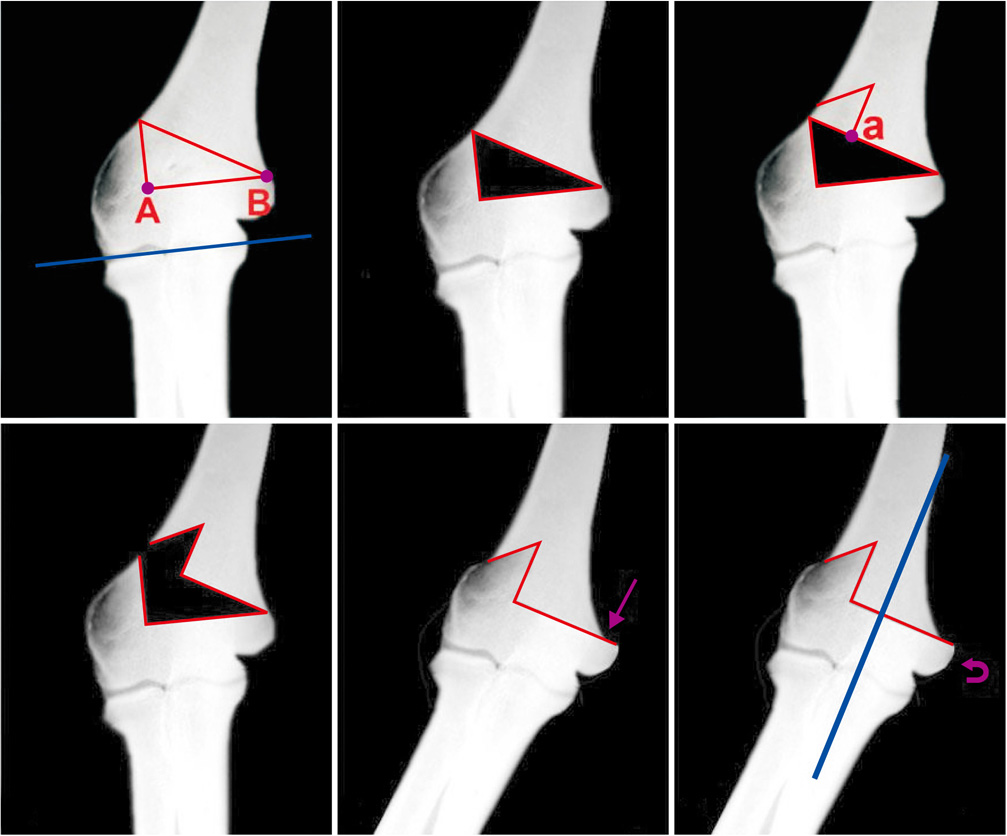

Fig. 3

Step-cut osteotomy. Cited from the article of Moradi et al. (Clin Orthop Relat Res, 471: 1564-1571, 2013) with original copyright holder's permission.13)

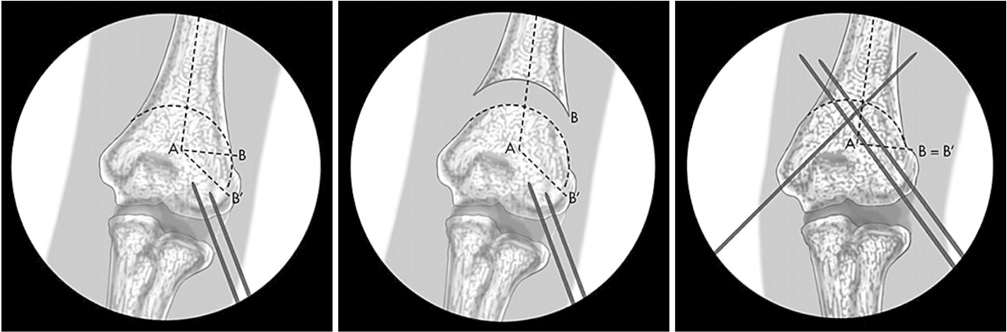

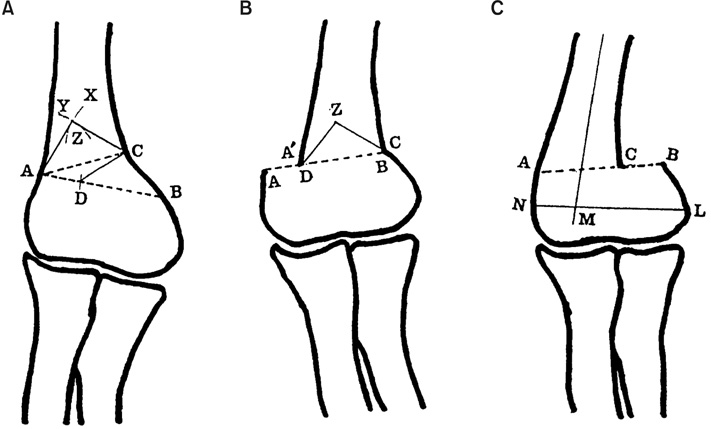

Fig. 4

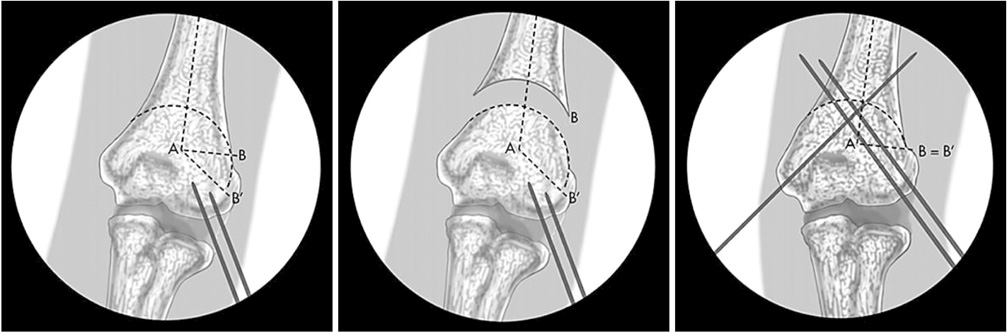

The dome osteotomy. Point A marks the intersection of the midline axis of the humerus with the olecranon fossa. AB is drawn perpendicular to the midline axis of the humerus. AB' is drawn parallel to the (altered) distal humeral joint line, so that the angle BAB' marks the angle needed for correction. The dome is then drawn with line AB' as its radius. After the dome osteotomy is completed, the distal humerus is rotated so that B and B' are the same point. Cited from the article of Bauer et al. (J Hand Surg Am, 41: 447-452, 2016) with original copyright holder's permission.16)

Fig. 5

Three-dimensional osteotomy. Dotted lines represent the planned osteotomies, which are made using preformed patient-specific cutting guides. Cited from the article of Bauer et al. (J Hand Surg Am, 41: 447-452, 2016) with original copyright holder's permission.16)

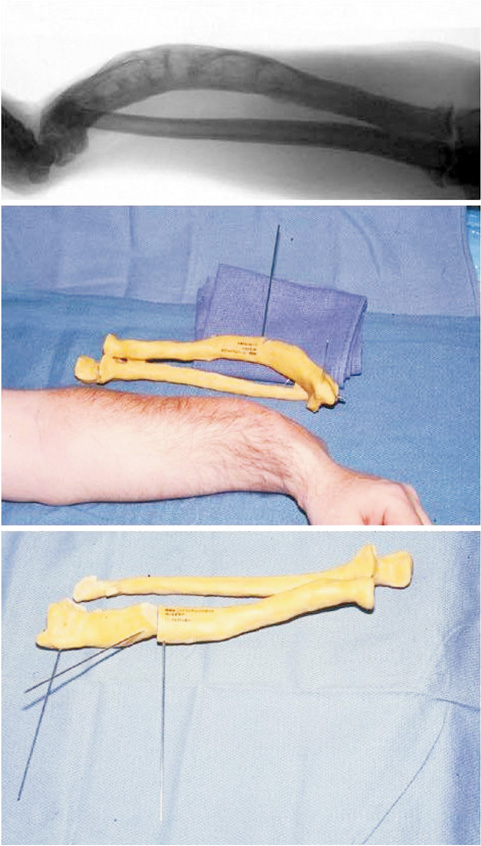

Fig. 6

Oblique corrective osteotomy for a malunited diaphyseal fracture of the forearm. Comparison radiograph—antero-posterior (AP) and lateral views of the left forearm malunion and the normal contralateral side. Clinical demonstration of preoperative rotational profile. Operative technique with exposure of the malunion site, plate contouring, oblique osteotomy and stabilization of the osteotomy site. Postoperative radiographs—AP and lateral views as well as a postoperative range of motion. Cited from the article of Jayakumar and Jupiter (Hand (N Y), 9: 265-273, 2014) with original copyright holder's permission.25)

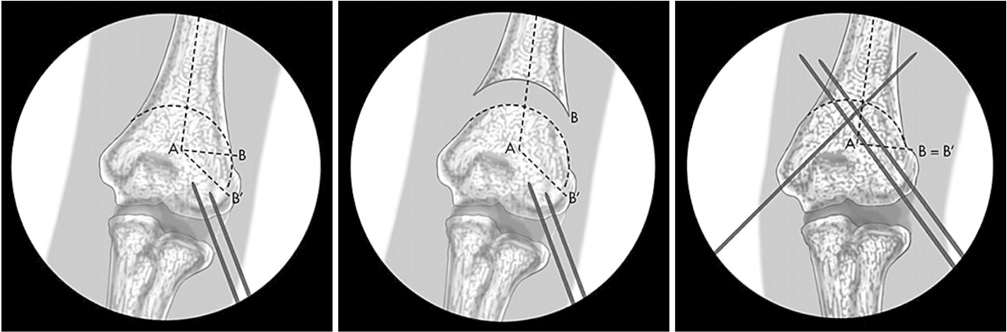

Fig. 7

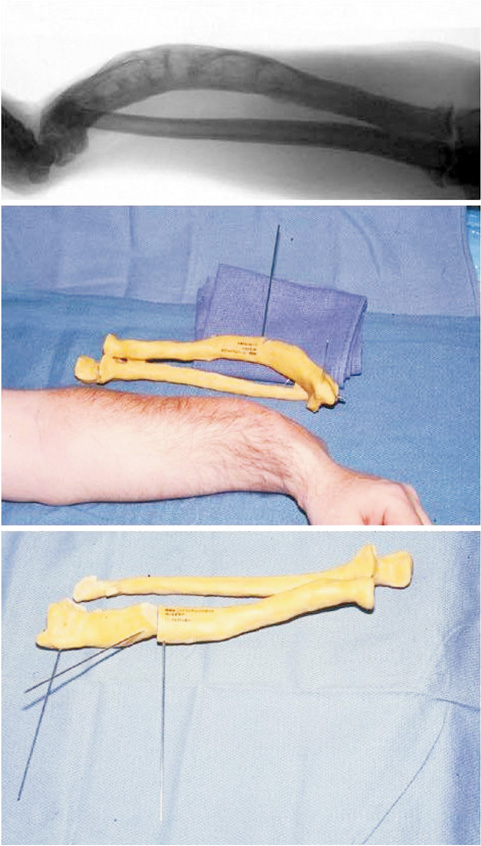

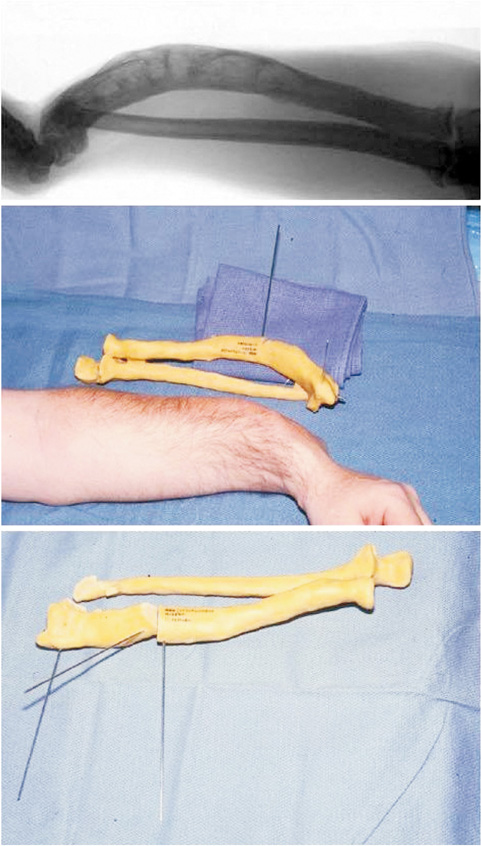

Single-cut corrective osteotomy for a malunited diaphyseal fracture of the forearm. Preoperative clinical image and radiograph of a complex malunion of the forearm. Computed tomography-guided development of a plastic model of deformity to aid preoperative surgical planning and simulation of bone wedge excision in the true plane of deformity. Operative technique with exposure of the malunion site, single-cut osteotomy, temporary stabilisation with external fixator and definitive plate stabilisation of the osteotomy site. Postoperative radiographs—antero-posterior and lateral views. Cited from the article of Jayakumar and Jupiter (Hand (N Y), 9: 265-273, 2014) with original copyright holder's permission.25)

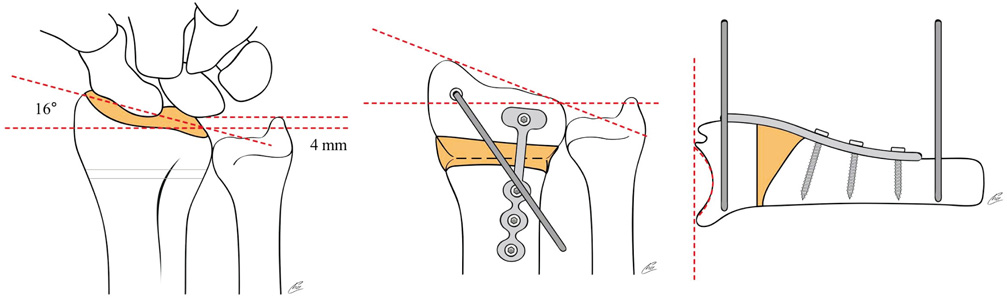

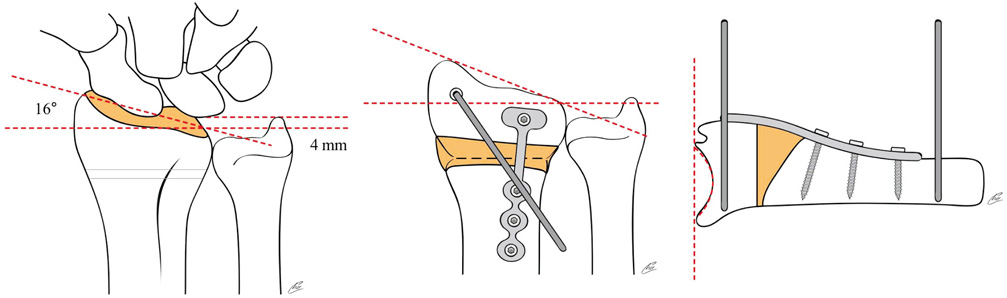

Fig. 9

Preoperative planning for the opening wedge dorsal osteotomy and fixation with the minicondylar plate.

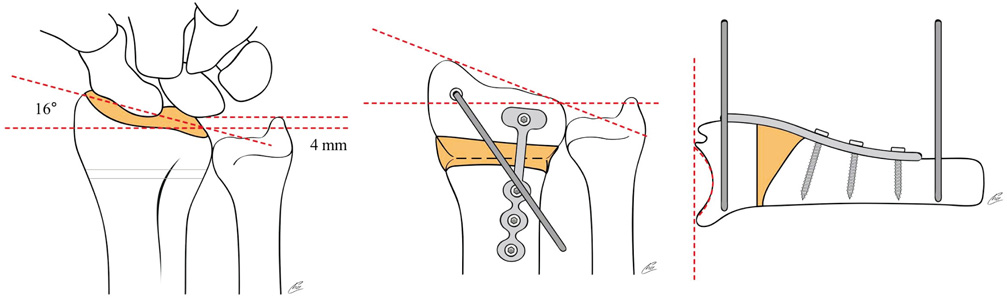

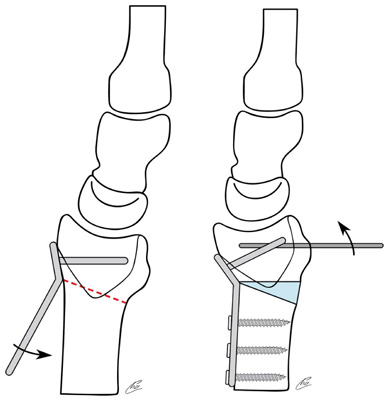

Fig. 10

Preoperative radiographs and planning: An opening wedge osteotomy was performed via a volar approach and fixed with a fixedangle plate and morcellized cancellous bone. Preapplication of the fixed-angle plate to the distal fragment at the anticipated angle of correction with two parallel pegs allowed the surgeon to subsequently remove the plate, make the osteotomy, and then reattach the plate to precisely rotate the distal fragment.

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

Malunion: Deformity Correction of the Upper Extremity

Fig. 1

Model of lIizarov apparatus for lengthening of the humerus.

Fig. 2

Schemati drawing of supracondylar quadrilateral displacement osteotomy. (A) ∠CAB: correction angle BC=CZ, DC=AZ, ΔAZC: DCB, □ZADC: being removed part. (B) After supracondylar quadrilateral displacement osteotomy, the distal fragment was medially displaced (AD distance) and wedge (AZC) was formed on line AC. (C) After French osteotomy (lateral closing wedge osteotomy), the prominence of lateral condyle becomes positive (author's method).

Fig. 3

Step-cut osteotomy. Cited from the article of Moradi et al. (Clin Orthop Relat Res, 471: 1564-1571, 2013) with original copyright holder's permission.13)

Fig. 4

The dome osteotomy. Point A marks the intersection of the midline axis of the humerus with the olecranon fossa. AB is drawn perpendicular to the midline axis of the humerus. AB' is drawn parallel to the (altered) distal humeral joint line, so that the angle BAB' marks the angle needed for correction. The dome is then drawn with line AB' as its radius. After the dome osteotomy is completed, the distal humerus is rotated so that B and B' are the same point. Cited from the article of Bauer et al. (J Hand Surg Am, 41: 447-452, 2016) with original copyright holder's permission.16)

Fig. 5

Three-dimensional osteotomy. Dotted lines represent the planned osteotomies, which are made using preformed patient-specific cutting guides. Cited from the article of Bauer et al. (J Hand Surg Am, 41: 447-452, 2016) with original copyright holder's permission.16)

Fig. 6

Oblique corrective osteotomy for a malunited diaphyseal fracture of the forearm. Comparison radiograph—antero-posterior (AP) and lateral views of the left forearm malunion and the normal contralateral side. Clinical demonstration of preoperative rotational profile. Operative technique with exposure of the malunion site, plate contouring, oblique osteotomy and stabilization of the osteotomy site. Postoperative radiographs—AP and lateral views as well as a postoperative range of motion. Cited from the article of Jayakumar and Jupiter (Hand (N Y), 9: 265-273, 2014) with original copyright holder's permission.25)

Fig. 7

Single-cut corrective osteotomy for a malunited diaphyseal fracture of the forearm. Preoperative clinical image and radiograph of a complex malunion of the forearm. Computed tomography-guided development of a plastic model of deformity to aid preoperative surgical planning and simulation of bone wedge excision in the true plane of deformity. Operative technique with exposure of the malunion site, single-cut osteotomy, temporary stabilisation with external fixator and definitive plate stabilisation of the osteotomy site. Postoperative radiographs—antero-posterior and lateral views. Cited from the article of Jayakumar and Jupiter (Hand (N Y), 9: 265-273, 2014) with original copyright holder's permission.25)

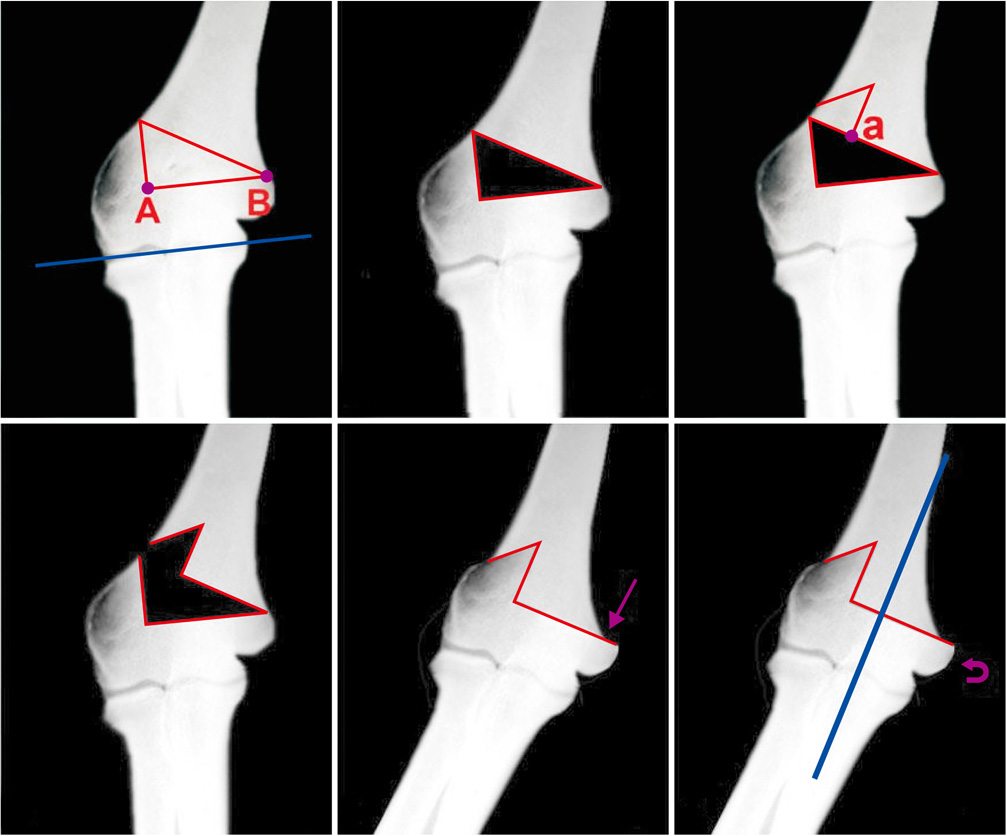

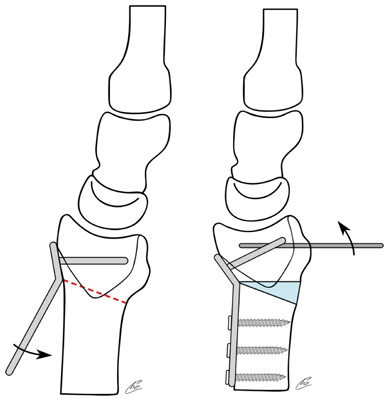

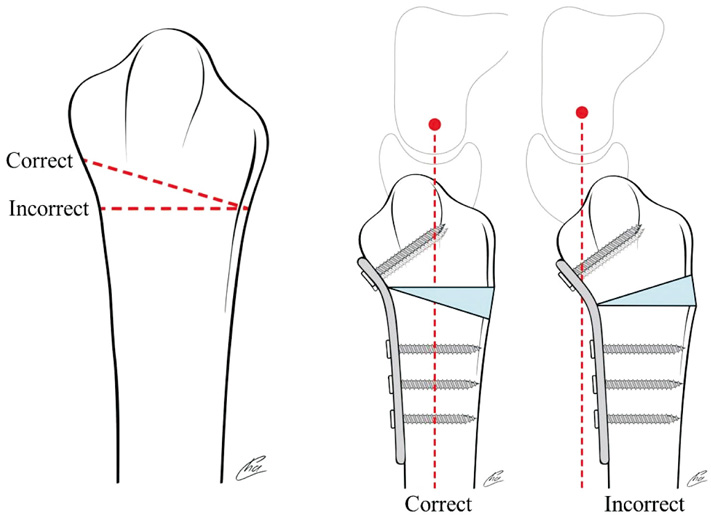

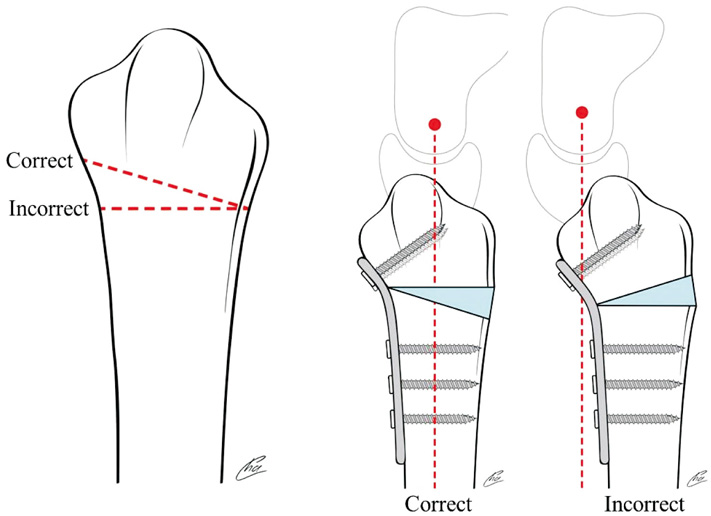

Fig. 8

Osteotomy must be parallel to the articular surface to avoid creating a secondary deformity.

Fig. 9

Preoperative planning for the opening wedge dorsal osteotomy and fixation with the minicondylar plate.

Fig. 10

Preoperative radiographs and planning: An opening wedge osteotomy was performed via a volar approach and fixed with a fixedangle plate and morcellized cancellous bone. Preapplication of the fixed-angle plate to the distal fragment at the anticipated angle of correction with two parallel pegs allowed the surgeon to subsequently remove the plate, make the osteotomy, and then reattach the plate to precisely rotate the distal fragment.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Malunion: Deformity Correction of the Upper Extremity

E-submission

E-submission KOTA

KOTA TOTA

TOTA TOTS

TOTS

Cite

Cite