Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Musculoskelet Trauma > Volume 28(2); 2015 > Article

-

Review Article

- Surgical Timing of Treating Pediatric Trauma: Urgencies/Emergencies

- Chang-Wug Oh, M.D., Ph.D., Joon-Woo Kim, M.D., Ph.D., Jong-Chul Lee, M.D.

-

Journal of the Korean Fracture Society 2015;28(2):146-154.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.12671/jkfs.2015.28.2.146

Published online: April 21, 2015

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea.

- Address reprint requests to: Chang-Wug Oh, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, 680 Gukchaebosang-ro, Jung-gu, Daegu 700-842, Korea. Tel: 82-53-420-5630, Fax: 82-53-422-6605, cwoh@knu.ac.kr

Copyright © 2015 The Korean Fracture Society. All rights reserved.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 317 Views

- 0 Download

- 1. Lee SC, Shim JS. Recent trends in treatment of supracondylar fracture of distal humerus in children. J Korean Fract Soc, 2012;25:82-93.

- 2. Skaggs DL, Mirzayan R. The posterior fat pad sign in association with occult fracture of the elbow in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1999;81:1429-1433.

- 3. Shim JS, Lee YS. Treatment of completely displaced supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children by cross-fixation with three Kirschner wires. J Pediatr Orthop, 2002;22:12-16.

- 4. Gupta N, Kay RM, Leitch K, Femino JD, Tolo VT, Skaggs DL. Effect of surgical delay on perioperative complications and need for open reduction in supracondylar humerus fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop, 2004;24:245-248.

- 5. Mehlman CT, Strub WM, Roy DR, Wall EJ, Crawford AH. The effect of surgical timing on the perioperative complications of treatment of supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2001;83:323-327.

- 6. Ramachandran M, Skaggs DL, Crawford HA, et al. Delaying treatment of supracondylar fractures in children: has the pendulum swung too far? J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2008;90:1228-1233.

- 7. Oh CW, Park BC, Kim PT, Park IH, Kyung HS, Ihn JC. Completely displaced supracondylar humerus fractures in children: results of open reduction versus closed reduction. J Orthop Sci, 2003;8:137-141.

- 8. Suh SW, Oh CW, Shingade VU, et al. Minimally invasive surgical techniques for irreducible supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Acta Orthop, 2005;76:862-866.

- 9. Oh CW, Park BC, Ihn JC, Kyung HS. Fracture separation of the distal humeral epiphysis in children younger than three years old. J Pediatr Orthop, 2000;20:173-176.

- 10. Song KS, Kang CH, Min BW, Bae KC, Cho CH, Lee JH. Closed reduction and internal fixation of displaced unstable lateral condylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2008;90:2673-2681.

- 11. Song KS, Shin YW, Oh CW, Bae KC, Cho CH. Closed reduction and internal fixation of completely displaced and rotated lateral condyle fractures of the humerus in children. J Orthop Trauma, 2010;24:434-438.

- 12. Song KS, Ramnani K, Bae KC, Cho CH, Lee KJ, Son ES. Indirect reduction of the radial head in children with chronic Monteggia lesions. J Orthop Trauma, 2012;26:597-601.

- 13. Jeong C, Park I. Treatment of neglected monteggia fracture in children. J Korean Fract Soc, 2012;25:233-239.

- 14. Song KS. Displaced fracture of the femoral neck in children: open versus closed reduction. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2010;92:1148-1151.

- 15. Dahl WJ, Silva S, Vanderhave KL. Distal femoral physeal fixation: are smooth pins really safe? J Pediatr Orthop, 2014;34:134-138.

REFERENCES

Fig. 1

Pucker sign. The sharp edge of the proximal fragment penetrates into the subcutaneous tissue (arrow).

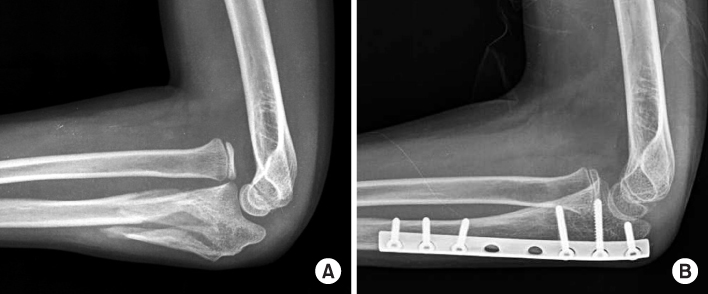

Fig. 2

Undisplaced fracture of the distal humerus shows the fat pad sign (arrow) around the posterior aspect of the elbow. It is an important sign when the invisible fracture is suspicious.

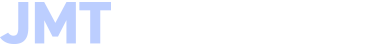

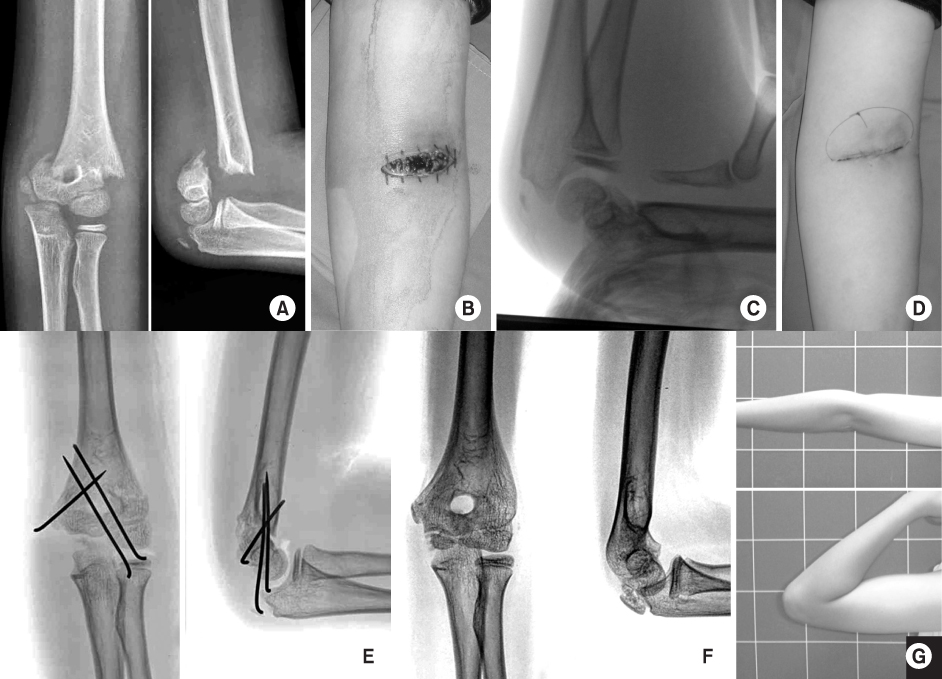

Fig. 3

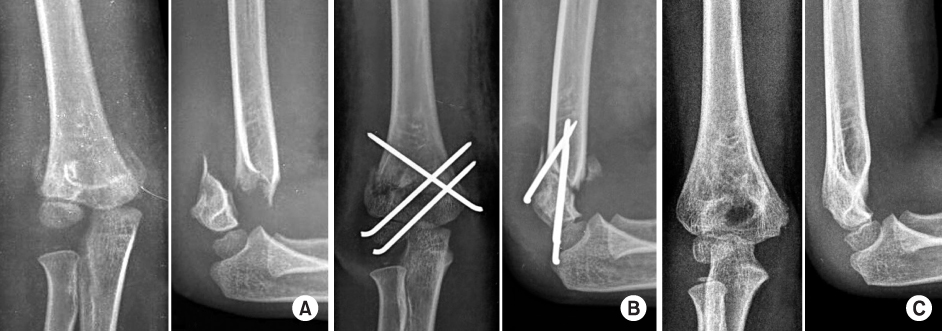

(A) A completely displaced fracture (Gartland III) of a 7-year-old boy. (B) After closed reduction, percutaneous pinning was performed with 3 pins. (C) A satisfactory alignment was achieved at 6 months postoperatively.

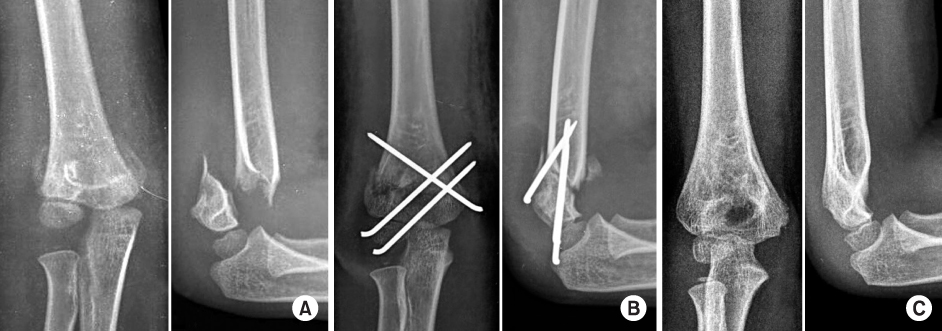

Fig. 4

After failure of closed reduction for a displaced supracondyar fracture (A), an anterior approach was used to reduce it (B, C), and to fix it percutaneously (D, E). At 8 months, an excellent functional outcome was achieved with a satisfactory alignment (F, G).

Fig. 5

An anterior-posterior elbow view of a 14-month-old boy shows that the proximal radius and ulna are displaced to the medial side (arrows). However, the central line of the radius (dot line) passes the center of the capitellum, which means not the lateral condyle fracture. As the lateral view of the elbow shows a small distal fragment, it is a fracture-separation of distal humeral physis.

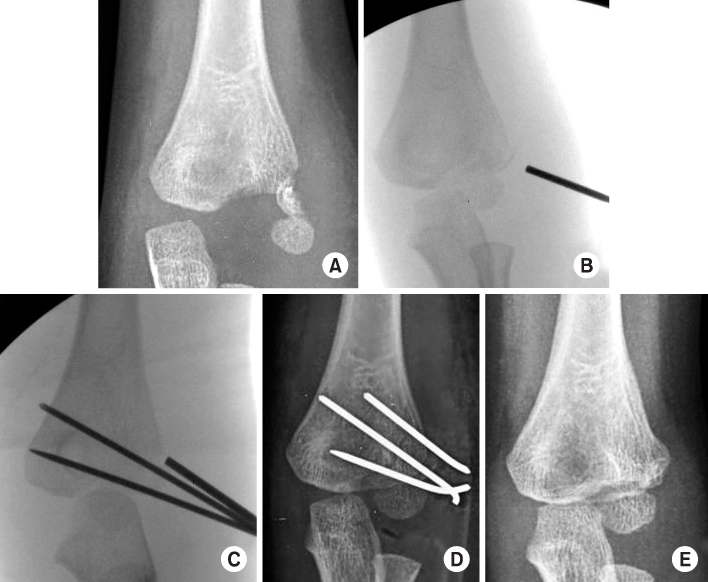

Fig. 6

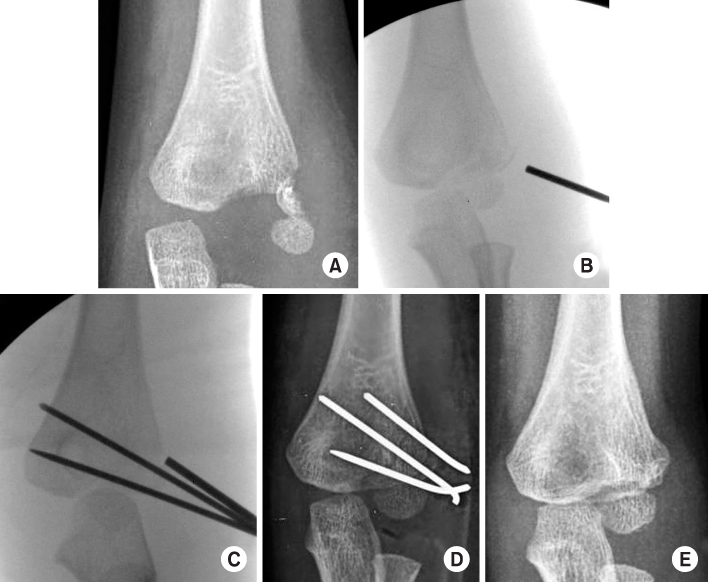

A completely displaced fracture of the lateral condyle (A) was reduced with closed manipulation (B) and fixed with K-wires. (C) A satisfactory reduction was gained (D), and the union was achieved at 6 months (E).

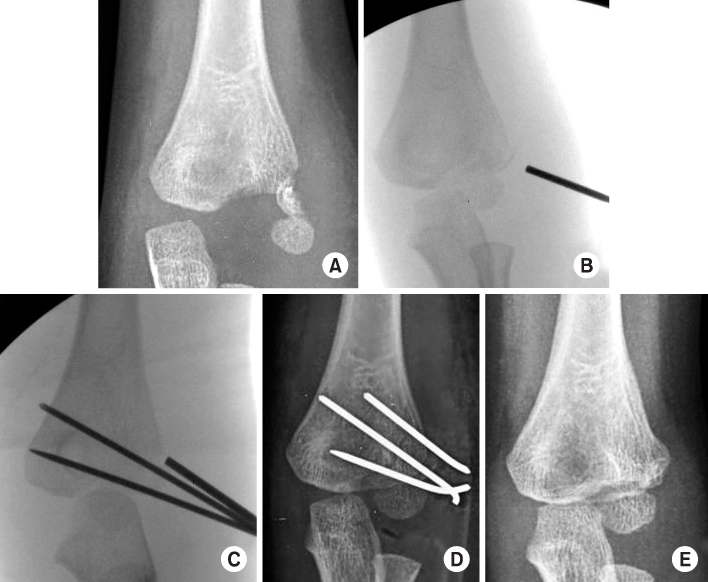

Fig. 7

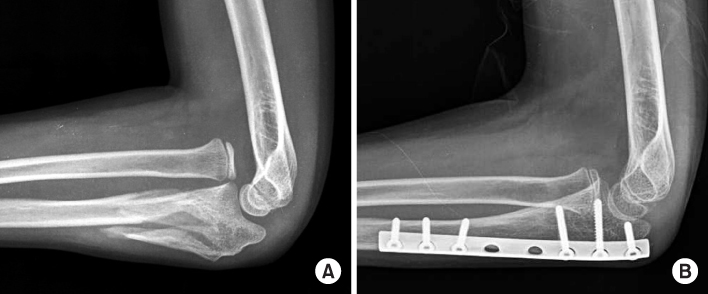

(A) A Bado type IMonteggia fracture. (B) After internal fixation with a plate, the radial head was anatomically reduced.

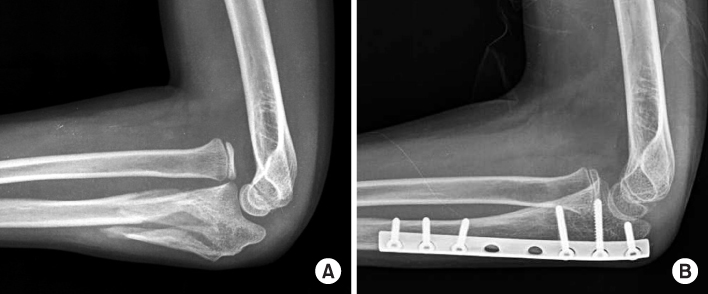

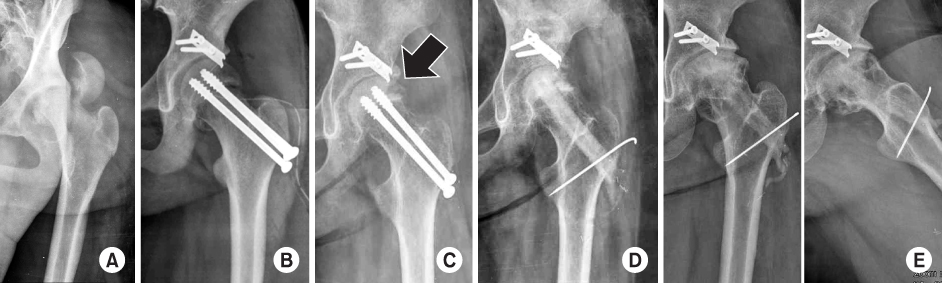

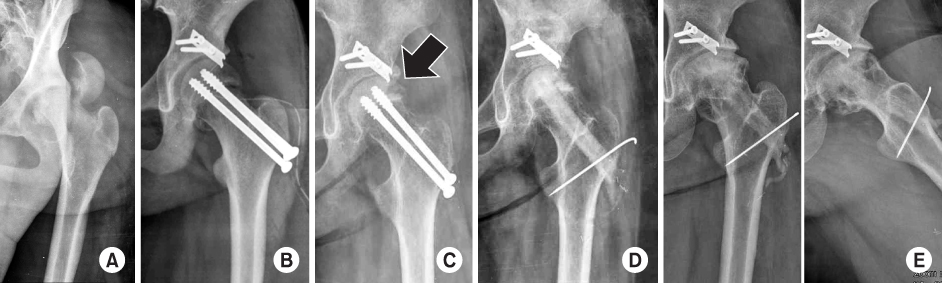

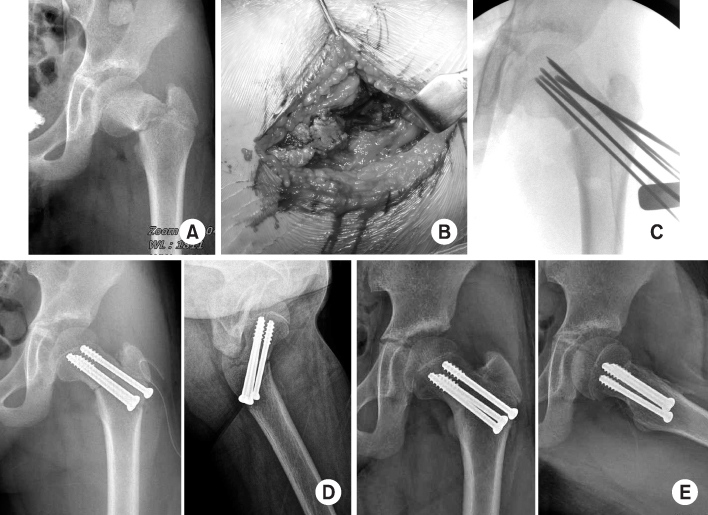

Fig. 8

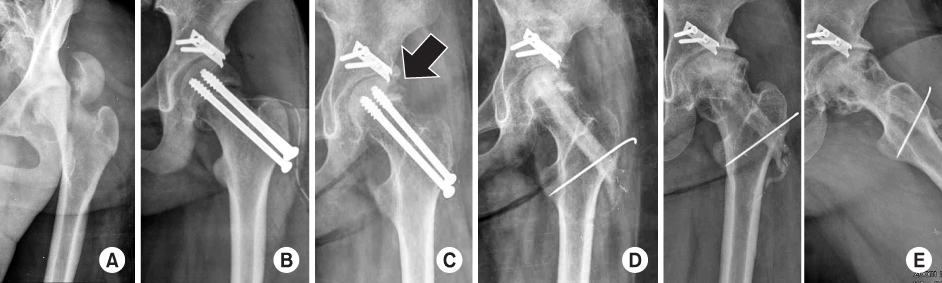

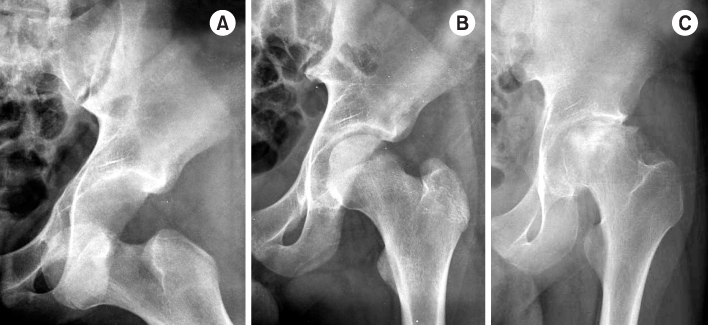

A completely displaced (Delbet type I) femur neck in a 12-year-old girl (A). Open reduction and internal fixation was performed (B), but avascular necrosis developed at 4 months (arrow) (C). Vascular fibular graft was performed (D) as a salvage procedure. At 9 years, the joint was preserved with a satisfactory function (E).

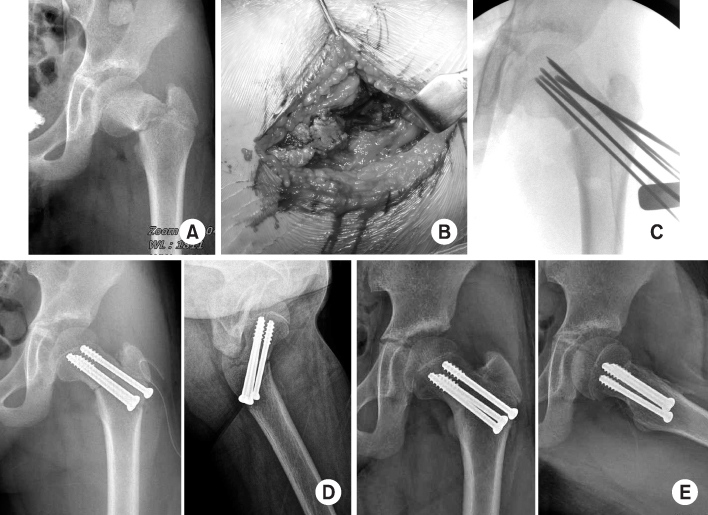

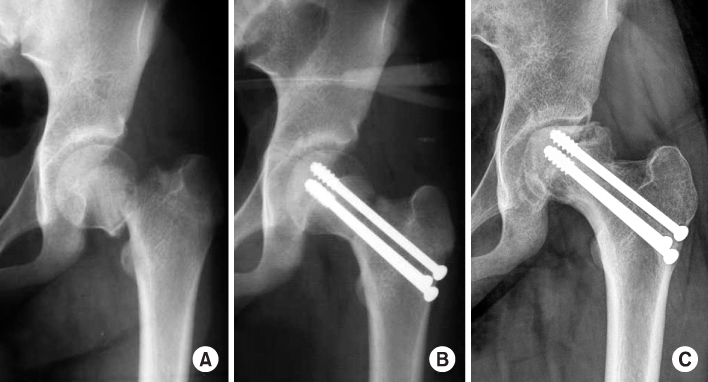

Fig. 9

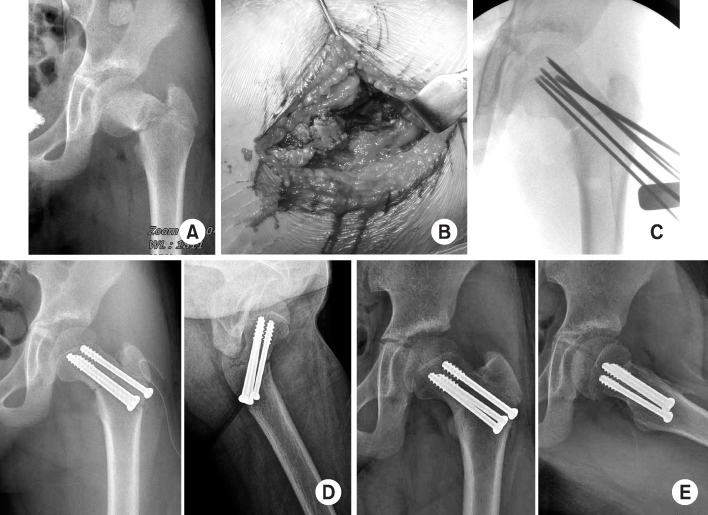

A displaced femoral neck fracture (A) (11-year-old girl) underwent multiple screw fixation after open reduction (B, C). A satisfactory reduction was achieved (D), followed by the uneventful union without avascular necrosis (E).

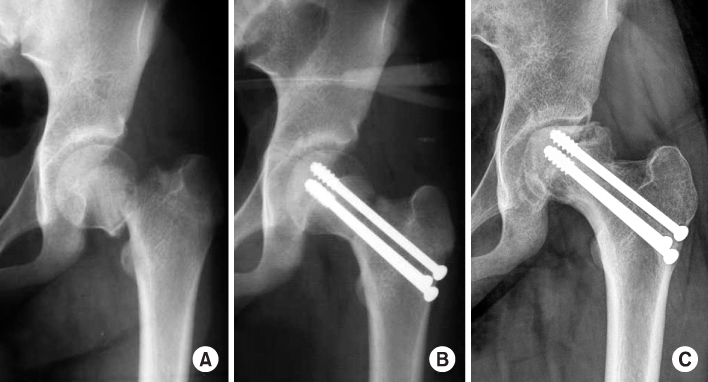

Fig. 10

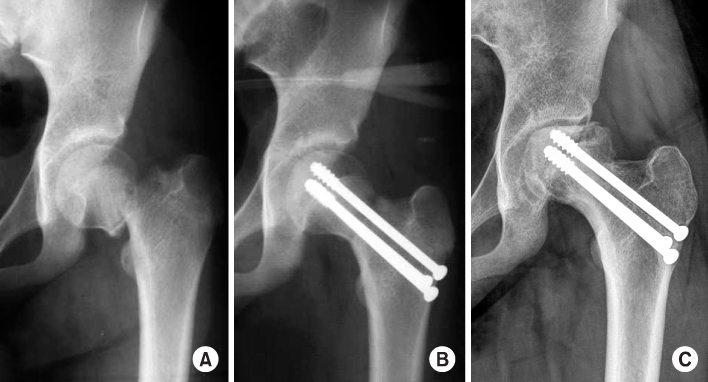

A type II femoral neck fracture (A) treated with screw fixation (B). Although the union was achieved, a partial type of avascular necrosis occurred at 6 months (C).

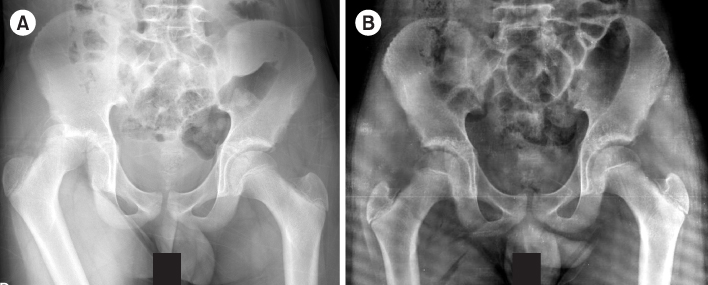

Fig. 11

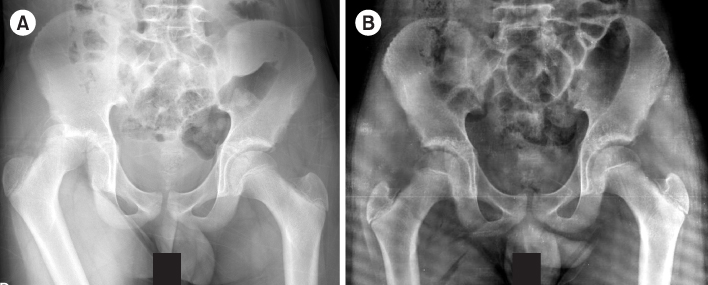

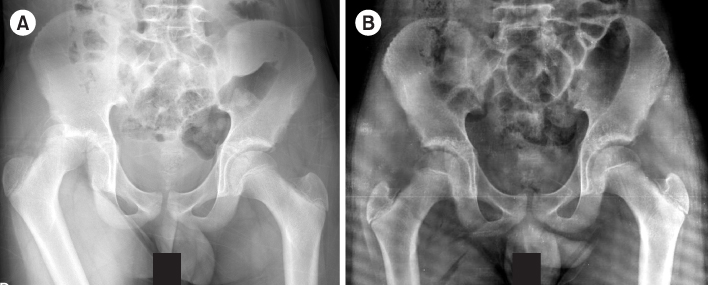

(A) A posterior hip dislocation of a 12-year-old boy. (B) The well-reduced hip after closed reduction.

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

Surgical Timing of Treating Pediatric Trauma: Urgencies/Emergencies

Fig. 1

Pucker sign. The sharp edge of the proximal fragment penetrates into the subcutaneous tissue (arrow).

Fig. 2

Undisplaced fracture of the distal humerus shows the fat pad sign (arrow) around the posterior aspect of the elbow. It is an important sign when the invisible fracture is suspicious.

Fig. 3

(A) A completely displaced fracture (Gartland III) of a 7-year-old boy. (B) After closed reduction, percutaneous pinning was performed with 3 pins. (C) A satisfactory alignment was achieved at 6 months postoperatively.

Fig. 4

After failure of closed reduction for a displaced supracondyar fracture (A), an anterior approach was used to reduce it (B, C), and to fix it percutaneously (D, E). At 8 months, an excellent functional outcome was achieved with a satisfactory alignment (F, G).

Fig. 5

An anterior-posterior elbow view of a 14-month-old boy shows that the proximal radius and ulna are displaced to the medial side (arrows). However, the central line of the radius (dot line) passes the center of the capitellum, which means not the lateral condyle fracture. As the lateral view of the elbow shows a small distal fragment, it is a fracture-separation of distal humeral physis.

Fig. 6

A completely displaced fracture of the lateral condyle (A) was reduced with closed manipulation (B) and fixed with K-wires. (C) A satisfactory reduction was gained (D), and the union was achieved at 6 months (E).

Fig. 7

(A) A Bado type IMonteggia fracture. (B) After internal fixation with a plate, the radial head was anatomically reduced.

Fig. 8

A completely displaced (Delbet type I) femur neck in a 12-year-old girl (A). Open reduction and internal fixation was performed (B), but avascular necrosis developed at 4 months (arrow) (C). Vascular fibular graft was performed (D) as a salvage procedure. At 9 years, the joint was preserved with a satisfactory function (E).

Fig. 9

A displaced femoral neck fracture (A) (11-year-old girl) underwent multiple screw fixation after open reduction (B, C). A satisfactory reduction was achieved (D), followed by the uneventful union without avascular necrosis (E).

Fig. 10

A type II femoral neck fracture (A) treated with screw fixation (B). Although the union was achieved, a partial type of avascular necrosis occurred at 6 months (C).

Fig. 11

(A) A posterior hip dislocation of a 12-year-old boy. (B) The well-reduced hip after closed reduction.

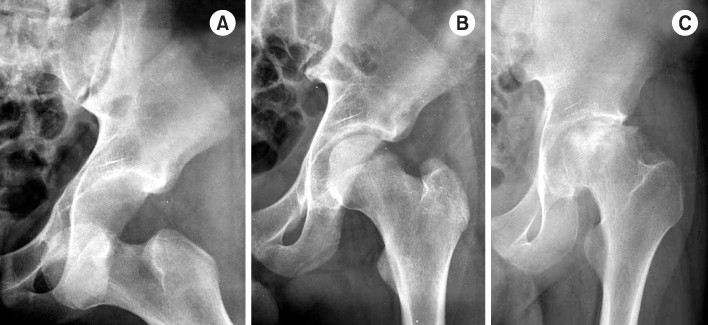

Fig. 12

An anterior hip dislocation (A) was reduced closely (B). However, avascular necrosis occurred at 6 months (C).

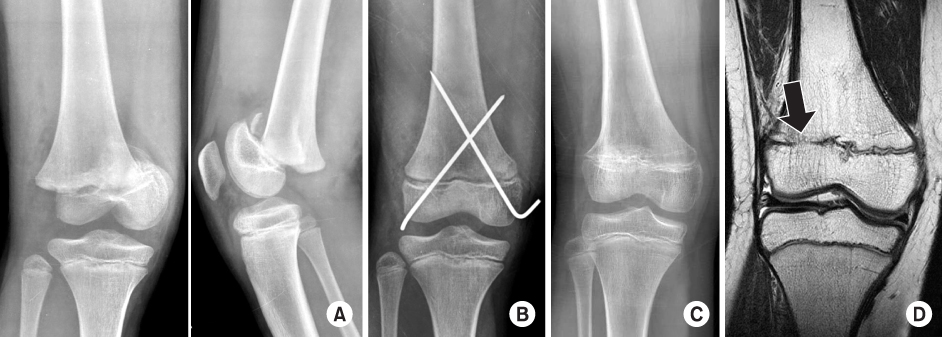

Fig. 13

A fracture at the physis of the distal femur in a 12-year-old boy (A) was reduced and fixed with K-wires (B). At 6 months postoperatively, a valgus deformity (C) developed with the physeal arrest on the magnetic resonance imaging (arrow) (D).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Surgical Timing of Treating Pediatric Trauma: Urgencies/Emergencies

E-submission

E-submission KOTA

KOTA TOTA

TOTA TOTS

TOTS

Cite

Cite